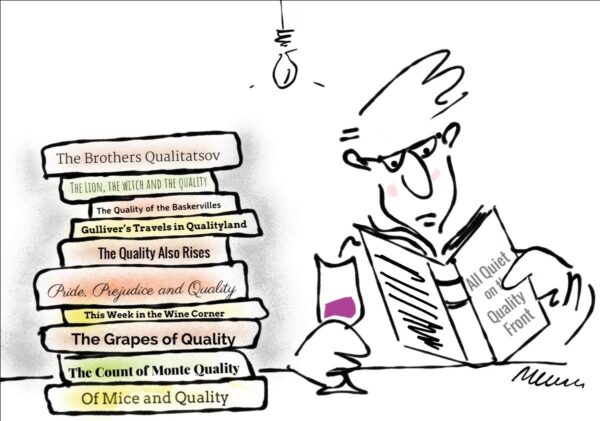

It’s no mystery that quality is a rather mysterious concept; one of those things everyone understands perfectly until it’s time to define it. Judgments of quality in wine are particularly challenging because we’re so easily distracted by the price of a thing or what we like or don’t like. But quality doesn’t depend on either of these.

Sometimes quality in wine is thought of as just more. But quality has this funny self-regulating aspect: At some point more necessarily becomes excess, and quality falls off.

In the wine corner, we’re convinced that any wine made from a proven varietal grown in an appropriate place under the eye of a responsible winemaker should be able to deliver quality, and that it can be spotted in the glass. Let’s think about how that can happen. Bear in mind that the subject here isn’t elite wine – just proper wine of any sort.

Quality means enough wine in the wine. The phrase comes from British wine guru Jancis Robinson who in one of her early books defined ‘body’ as ‘how much wine is in the wine.’ When tasting, it’s almost always the first thing one notices. Per above, more body is not necessarily better than less (that’s generally a style issue), but it’s fundamental that the amount of fruit each vine is asked to ripen must be of an order to concentrate flavors and aromas to a satisfying degree. Overproduction degrades quality.

Quality tastes like a chord sounds. I refer to the way a chord presents a cluster of musical notes occurring either simultaneously or in such quick succession that they give nearly the same effect. A proper wine generates a similar experience by eliciting a burst of sensations that (1) ‘sound right’, (2) aren’t readily parsable into discrete elements and (3) endure for some moments before resolving into a succession of ever-fainter echoes. The chord needn’t be of Wagnerian complexity. A simple three-note job will do.

Quality evinces appropriate scale and proportion. When fruit, acidity, alcohol and tannin (if present) coexist in such a way that each is a team player, you have something wine tasters call balance. All good, but this ignores the seemingly obvious point that a too-big wine can be balanced but still be just too damned big. It’s also true that if you had two enormous arms, you’d be balanced, but not really well-proportioned. Scale and proportion count for a lot.

Quality energizes, rather than fatigues. Here’s a simple one. Wine’s primary task is to refresh the palate at meals and keep us moving with enthusiasm from course to course. Yes, not all wine is enjoyed as part of a multi-course dinner, but in every case wine should be an appetizing thing, a kind of perpetual motion machine that generates its own momentum in the direction of what comes next. Wines that lack this essential feature are suspect in the quality department.

Quality sustains the interest it arouses. Proper wine has a way of arresting attention and holding on. The holding on part is critical because though winemakers have all kinds of tricks for initially seizing your attention, there are no tricks by which a wine can sustain interest from glass to glass and bottle to bottle, except by being genuinely and persistently engaging. Quality wines know this somehow, and don’t play games.

Quality isn’t always beautiful. There’s an intangible element that telegraphs quality in wine – that says here is something a conscientious winemaker put heart and soul into, abstaining from lame attempts to disguise faults and building in all the quality the assumed price point allows. I can’t say how I sense this, and don’t pretend I’m always right about it, but I sometimes feel this strongly even when the wine isn’t entirely delightful or what we might call beautiful. That’s because — and this may be the hardest thing to get a grip on — quality and beauty aren’t always found together.

It’s true of people and its true of wine.