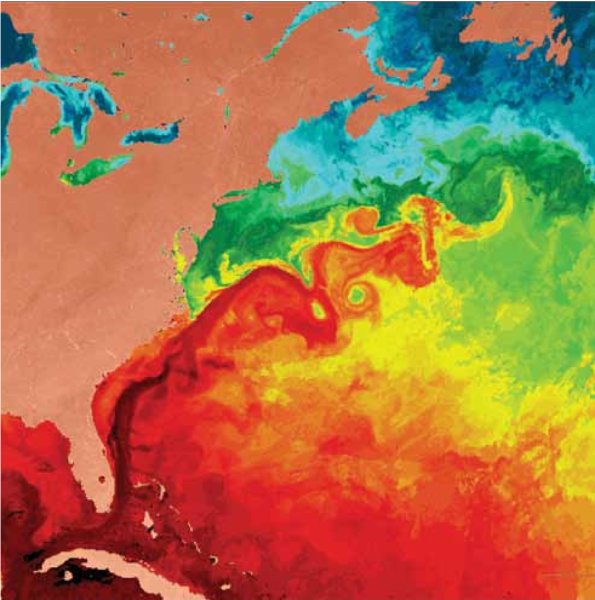

The picture above isn’t abstract expressionist art you might encounter in a Newbury Street gallery. It’s a thermal image of a section of the North Atlantic. The warm Gulf Stream appears as a red-orange streak separating the Sargasso Sea from the colder continental shelf. Coldest water is bluest; warmest is deepest red.

Thermal imaging takes phenomena we’re generally familiar with and presents it in an arrestingly fresh way. I’ve often wished for a tool like this that to graphically depict the degree to which things in the physical world have been overlaid with human ideas. By means of this make-believe technology, those things most richly endowed with human imagination would glow fiery red, while those with less would show cooler hues. I’m convinced that wine would register as vivid scarlet on any such map.

Why? Because from the beginning, we’ve embroidered wine’s semantic fabric with meanings that go far beyond quenching thirst or getting buzzed. Raise a glass of wine and you lift not just a pleasantly alcoholic brew of fermented fruit juice, but a few millennia worth of meanings, associations, references, allusions, symbols. Heated by the human imagination, wine fairly glows.

An early example of wine as sign is provided by its reception in the great cities of the ancient Near East in the third millennium BCE. As an expensive import from the hill country far to the north, wine set its devotees apart from ordinary folk as wealthy and socially significant, likely with connections to the royal court. Among the Greeks, wine and bread — as elaborated, rather than strictly natural, products — distinguished civilized, humane culture from mere animal life; while Bacchus, the enigmatic and petulant child-god of wine, took us out of ourselves and connected ordinary mortals with the divine and the ecstatic.

The Hebrews made important contributions. Genesis tells us that it was Noah who planted the first vineyard post-deluge (and became roaring drunk with the wine he made from it), while the Song of Solomon links wine directly with the pleasures of lovemaking and sensuality in general. In the Torah, one of the marks of God’s special favor is said to be an abundance of “new wine and oil.” To judge from this, wine is simultaneously dangerous, sexy, and a mark of blessing.

Romans drank wine to set themselves apart from Germans who preferred beer. Conversely, Celts eager to affect Roman-ness and be judged worthy to launch a career in the service of empire gave up their beer and adopted wine. When it comes to constructing social identities, wine is prime building material.

The notion that wine is elite and sacred and beer proletarian and secular has been a persistent motif in Western culture and highlights the degree to which ideas represent a kind of currency, readily exchangeable and quick to accrue fresh values by means of the binary contrasts they create. Either ale is a manly, virtuous drink and wine something morally dubious urban sophisticates indulge in; or wine is for nobs and ale for yobs. Either way, there’s a shot of self-representation in every sip.

The signs we post with wine aren’t just for the benefit of others. Sipping Dom Perignon won’t make you a rock star any more than taking a glass of sherry with a biscuit at 4 in the afternoon will make you an Oxford don, though either can make you feel the part, if ever so briefly.

What a wonderfully fertile heap of cultural compost wine turns out to be. Centuries deep, whimsical and reasoned, sacred and profane, mostly coherent, endlessly useful —and still hot after all these years.