The bold adventurers who first landed on the shores of what they thought of as the New World didn’t come alone. The newcomers brought horses and pigs to the Americas, and returned bearing the potatoes, tomatoes, squashes and maize that would subsequently enrich the diet of generations of Europeans. Though the Americas had native grapevines aplenty, they didn’t make the kind of wine considered suitable for the celebration of the Mass or the tables of gentlefollk. Vitis vinifera, Europe’s historic winemaking vine, was imported to fill the gap. Mostly, it failed to thrive. It wasn’t clear why.

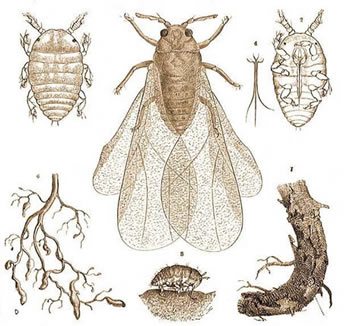

The culprit, in many cases, was an aphid-like insect, nearly microscopic in its most dangerous life-stages, that attacked and sucked the life out of the defenseless European transplants. Phylloxera vastatrix, as it is known, was long endemic here, but native vines like the riparia and rupestris species had evolved resistance to its worst predations. It was bad enough that Europeans failed repeatedly in their attempts to cultivate vinifera vines in America, but in the 19th century steamships cut the travel time between continents to just a week or two — a short enough time for phylloxera mites on American vine cuttings to survive the journey and set about ravaging European viticulture. It’s as if the New World had said “Thanks for the smallpox and syphilis, Old World. Here’s a little something for you.”

The upshot is that after a frightening brush with total collapse, the European wine industry was rescued by the previously cited phylloxera-resistant American rootstock, onto which, by the turn of the 20th century, almost the entirety of Europe’s vinifera vines had been grafted. It’s a dramatic, hair’s breadth escape kind of tale, but one whose most significant long-lasting consequences are frequently overlooked.

It’s rare that an embedded industry of any sort, never mind one that has been in place for more than a millennium, gets a chance to completely reinvent itself. But, in the wake of phylloxera, that’s exactly what happened. Government money poured into the grafting effort, and winegrowers had the opportunity to decide what varietals they wanted to bet their futures on. The result was a substantial uptick in rational, scientific agronomy but it came at a high price: the disappearance of who knows how many heritage cultivars in favor of others known to be more productive, more marketable, easier to grow, and, of course more profitable.

It was only after Europe’s great vineyard do-over was complete that the first appellations were established, in many cases giving the force of law to decisions that had been made as recently as a few decades before. It’s as if great swaths of the ancient text known as The Book of Wine had been erased and written over in blander, less imaginative, more business-friendly prose. It’s a move none of us would have thought wise or even possible, but without this timely pestiferous intervention modern wine simply wouldn’t be what it is.

The moral of the story? Never underestimate the power of the tiniest of Earth’s creatures — even if this particular one happens to be a bit of a louse.

-Stephen Meuse

This week in the wine corner . . .

THURSDAY, JANUARY 31 3-6 PM – THIS PLACE IS BUGGED

Terraviva “Lui” Montepulciano d’Abruzzo, $23.95

Château Coupe Roses, “Vignals” Minervois, $21.95

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 1 3-6 PM – GENTLEFOLK APPROVED

2017 Bernard Baudry “Les Granges” Chinon, $21.95

2015 San Fereolo, “Valdibà” Dolcetto di Dogliani, $26.95