We’re not talking about Ball, Teale, Davis or Inman squares here (as you Cambervillians may be thinking). No, this is about conceptual squares and how what we’re calling Next Square Thinking can help you be a savvier, more adventurous wine consumer.

I say adventurous, but one of the nice things about NST (as I’ll refer to it) is how gently and naturally it can be used to expand your wine experience. Because you’re making subtle moves within a space that’s already familiar to you, there’s little risk.

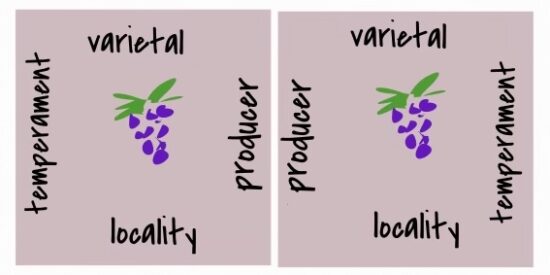

In the diagram at the top, you can see that the four edges that form the left square are labeled varietal, locality, producer, temperament (the order doesn’t matter). Together, the boundary labels identify some important features of a single wine, one you know and like.

The square on the right shares one boundary with the one on the left, the label of which we’ve moved into an adjacent position underscore the relationship. This shared label is “producer.” This second square represents a different wine, but which is a product of the same winemaker (or estate) as the first. The common “producer” boundary means this is a next square wine and trying it would be a small, logical, low-risk move.

But there are at least three more adjacent squares (not pictured) you could hop to equally reasonably — each sharing a boundary with your original square: the ones labeled varietal, locality and temperament. Each of these would lead you to a fresh set of squares, and by extension, wines.

Presumably, the more boundaries one square shares with another, the closer the kinship and sensory similarities are likely to be.

Of course, you can label the boundaries whatever you like, depending on the kind of exploration you have in mind. If, for example, you’re pleased by a wine selected by a particular importer, you could build some next squares on that criterion; or drill down into something as specific as a single vineyard site which might be shared by different producers (as is often the case in Burgundy); or get some experience of wines fermented by means of carbonic maceration (the label might be “technique”). You can use two labels on one shared boundary if doing so makes the connections clearer and gives you more options. It’s a highly flexible system.

Just how this might work in practice can be seen on our Loire Valley shelf where we typically have wines from what are known as the escarpment villages at its eastern end. There are five appellations of particular interest — Sancerre being the most well-known.*

Whites wines here are traditionally made exclusively with Sauvignon Blanc — so a varietal connection there — and have much in the way of temperament** in common. But each producer will have a proprietary approach, working with different expositions and soil types, younger and more mature vines, etc. This is a place where the adjacencies are particulary easy to parse.

NST is most useful when its objects have a few things in common and a few things that represent variation, so you have both elements in common and possibilities for movement. Of course, we’re not advising you to start literally diagramming wine. This all takes place in the realm of imagination and conversation.

Some of you may find this all familiar, even if the vocabulary is new. Others will recognize the approach as one we often take when chatting with clientèle in the way of “if you liked X you may want to try Y.” If it’s a novel idea to you, consider that thinking this way might just take your wine experience to another level.

Or is it a next square?