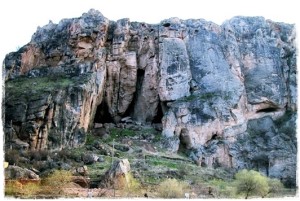

ARENI, ARMENIA. As caves go it’s not the sort to attract attention. There are no souvenir shops on the approach and no dramatic lighting within intended to highlight the kind of fantastic calcified structures that are so beloved of spelunker-wannabe tourists. There is only a vertical opening like a nasty unhealed wound in this ancient rock face in the mountains of southeast Armenia not far from the border with Iran.

The otherwise nondescript cave made big news, however, in 2011 when a team of archaeologists led by Professor Boris Gasparyan, co-director of the Armenian Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, announced that they had discovered in it the remnants of a winemaking facility dating back more than 6,000 years.

I knew about the cave and had written something about it in 2012, so was amazed when the opportunity came to visit it. I was even more thrilled to discover that our guide that day would be Professor Gasparyan himself.

To get an idea of the antiquity of the site, remember that in the fifth millennium BCE we are in the late neolithic era, still deep in pre-history, several thousand years from the invention of writing or of cities or of the kind of civilization that the discovery and development of agriculture would one day make possible.

In this period we can imagine that in some places at least, once-mobile bands of hunter-gatherers had settled down to practice a kind of proto-farming made possible in part by the development of pottery technology. Waterproof fired ceramic vessels meant grain could be safely stored from one harvest to the next and seed-stock preserved – but it also meant that fruit fermentations could be controlled and the resulting wine stored and even matured with later consumption in mind.

There’s plenty of material online about the cave and its contents, so I won’t rehearse that here. In its eagerness to make the story relevant for the average reader most press coverage of the site overlooks what is surely the most interesting aspect of the find: that the origins of wine have no connection whatever to gastronomy.

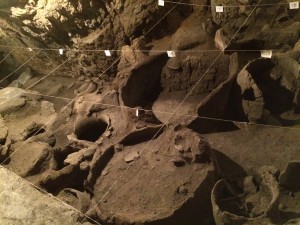

The cave is not fully excavated (and will not be in our lifetimes for reasons I will explain later) but one of the first things that strikes the visitor to the site is its small size. This was clearly not a facility built with a view to making significant volumes of wine (photo below). As Dr. G explained to our rather horrified group, the so-called winery was actually a site for the performance of fertility rituals aimed at ensuring that the cycle of agricultural activity (growth, ripening, harvest) would be repeated for another year.

Analysis of the pottery vats reveal that children were sacrificed here, their blood added to the pots of fermenting juice, which was then consumed by the community – or perhaps segments of it. Long, hollow reeds found at the bottom of several vats indicate that the new wine would have been sucked out soda fountain fashion via straws, perhaps while it was still fermenting. In other words, while it was still alive with CO2 gas. Sparkling wine, it seems, did not have to wait for the widow Clicquot.

Dr. Gasparyan had lots to say about the fact that wine appears to have originated as an important element in neolithic fertility rites and not primarily as an accompaniment to food. Wine’s original, neolithic meanings persist in Christian rites, such as the mass, he noted, where blood and wine are both closely related and magically interchanged.

As for the children, an analysis of their remains indicates that they were prepared for their deaths by being fed a special diet – an element with echoes in European fairy tale narratives that speak of witches fattening kidnapped children before baking them in an oven. In one, a child, asked to present his finger as a way for the blind witch to determine whether he was fat enough to cook, offered instead a chicken bone – a clever trick that bought him enough time to eventually make his escape.

There’s much more to be discovered in the cave, but by virtue of an international convention among archaeologists 30% of the site must be left unexplored. The idea is that since the technology for conducting these excavations is advancing at a rapid rate, it’s a better idea to leave some areas in virgin condition for a future generation of scientists to apply themselves to . . . and perhaps uncover fresh horrors.

Stephen Meuse can be reached at stephenmeuse@icloud.com