It seems laughable now, but in European theaters it was once common practice for the impresario to hire applauders for opening night. Claques, as they were called, were brought in to give it up enthusiastically for the playwright and cast at the end of the debut performance with a view to ensuring a long run. I don’t think we do this anymore — hey, it could be the entertainment business’s best-kept secret for all I know — but I have to admit that there have been nights at Symphony Hall when thunderous applause has convinced me that the performance I had just witnessed must have been truly extraordinary. While I enjoy classical music, I’m no Jeremy Eichler. If the audience is on its feet shouting bravos, it must have been great, right?

It’s hard to remain calm when all around you are losing their heads, and it’s equally hard to refrain from being swept up in the enthusiasm of a cheering crowd. I was giving this some thought recently as I pondered how it is that wine has changed so much in the decades since I first became an enthusiast. When I came in, the standard for really fine wine could be found in just three places: Bordeaux, Burgundy, and Champagne. There wasn’t much French wine from other regions, or much Italian wine, available in Boston well into the 1970’s and even the ’80’s.

Together these three regions provided the models for how proper, status-conferring wine was supposed to be made. In 1976, California pushed France to the wall in the tasting event that’s become known as The Judgment of Paris, with the result that the standing of American wine was enhanced. But making room for one more deity on wine’s version of Mt. Olympus didn’t really involve a revolution. Napa Valley was admitted to the Pantheon. But no one was questioning whether there should be a Pantheon.

Then came Robert M. Parker Jr. and his subscription newsletter, the Wine Advocate, which became quite possibly the most powerful publication influencing buying behavior with respect to a single consumable in American history. Parker’s authority first established and then confirmed on a bi-monthly basis the style of wine that was to be preferred over all others, and persuaded most of the wine-consuming world that he, as Claque-in-Chief, should determine what is applaudable and what isn’t. For Parker and his partisans, what wine is — how it should look, smell, taste, and feel — is a settled matter and progress consists of finding ways to make it incrementally more of what it already is.

The situation probably has many analogues, but the one that keeps coming back to me is The Salon, France’s long-standing, state-sponsored annual art exhibition that received a jolt in 1863 when a group of artists whose work had been refused by the jury protested their exclusion and subsequently staged their own exhibition in another part of the same building. The exhibit, became known as the Salon des Refusés. Today we might have styled it the Rejection Collection.

The official Salon set and maintained standards for good taste in painting and sculpture not just for France, but for all of Europe and America, too. They took a narrow view of both style and subject matter: the decorous still life, picturesque landscapes, portraits of distinguished persons, and historical subjects were approved, so long as they were rendered in what we would later call a photorealistic style. For the jury and those who followed its dictates, what constituted fine art was a settled matter and progress was conceived of as finding ways to make it incrementally more of what it already was.

Among the refusés mounting the counter-exhibition were a few names you might recognize: James McNeill Whistler, Gustav Courbet, Camille Pissarro, and Eduard Manet. By systematically rejecting work that failed to conform to its rather rigid standards the Salon pretty much guaranteed that the genetic material out of which modern art evolved would be drawn from the refusé pool, rather than from the cadre of establishment artists. It’s hard to think of an example when the essential antagonism that exists between conventionals and dissidents has been more clearly and colorfully drawn.

I can’t say that the evolution of wine will follow this same trajectory, but as things stand today the similarities are striking. Standing in for the Salon artists are those making wine in a conventional, internationally approved manner — professional, polished, deeply-colored (if red), rich in fruit and with a plush texture — and ready to avail itself of almost any technology that promises to enhance these features.

Standing in for the refusés, a somewhat motley collection of small-scale vintners who have little in common except a willingness to push the envelope of accepted practice, in many cases by turning back the clock to a kind of farming that predates the chemical era and to cellar practices that reflect a preference for letting nature take its course. With this group one can’t really speak of a single approach to winemaking or a single style of wine that’s being aimed at. Progress isn’t seen as incrementally more of what already is, but a continuous probing of boundaries to see what might be possible.

Visitors to the official Salon and its off-brand counterpart in 1863 weren’t just confronted with oppositional theories of how art should be done. The work itself looked startlingly different.

In the same way, new approaches to winemaking frequently yield dramatically different wines: reds that are generally lighter in body, with brighter, fresher acidity; whites characterized by savory rather than overtly fruity flavors and with the enhanced grip and deeper colors that come from maceration on the grape skins. A tendency to minimize the use of sulfur among these experimenters has so far had heterogeneous results, it seems to me: in some cases making the wine unusually vivid, in others seemingly dulling it.

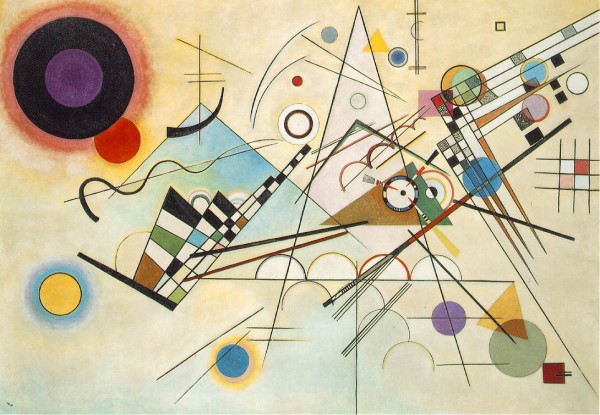

Whether this brave new world of winemaking will produce the equivalent of a Courbet, Pissarro, or Manet – or already has — I can’t say. What’s perhaps more interesting is whether it will ever produce a Picasso, Kandinsky, or Jackson Pollock.

What would an abstract expressionist wine taste like, I wonder, and would it represent progress?

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com

Follow Stephen Meuse