Throw in that it involves grapes that are never crushed and somehow ferment without the help of yeasts and you’re losing people by the minute. But as we discovered at a recent Thursday Night Wine Bar, some delicious wines are made this way, wines that show a spectrum of flavors and scents that aren’t achievable via more conventional techniques.

Carbonic maceration may sound newfangly and technological, but it’s far from it – so let’s begin with an explanation.

In conventional red wine fermentations, grapes are crushed (by foot or machine) breaking open the skins and releasing their juice. Everything – skins, seeds, stems if desired – then goes into a fermenting tank where a variety of yeasts (either naturally-occurring or commercially-prepared) feed on the grape sugars converting them to carbon dioxide and alcohol. Eventually a pressing separates juice from solids, and the new wine is put into barrel or tank.

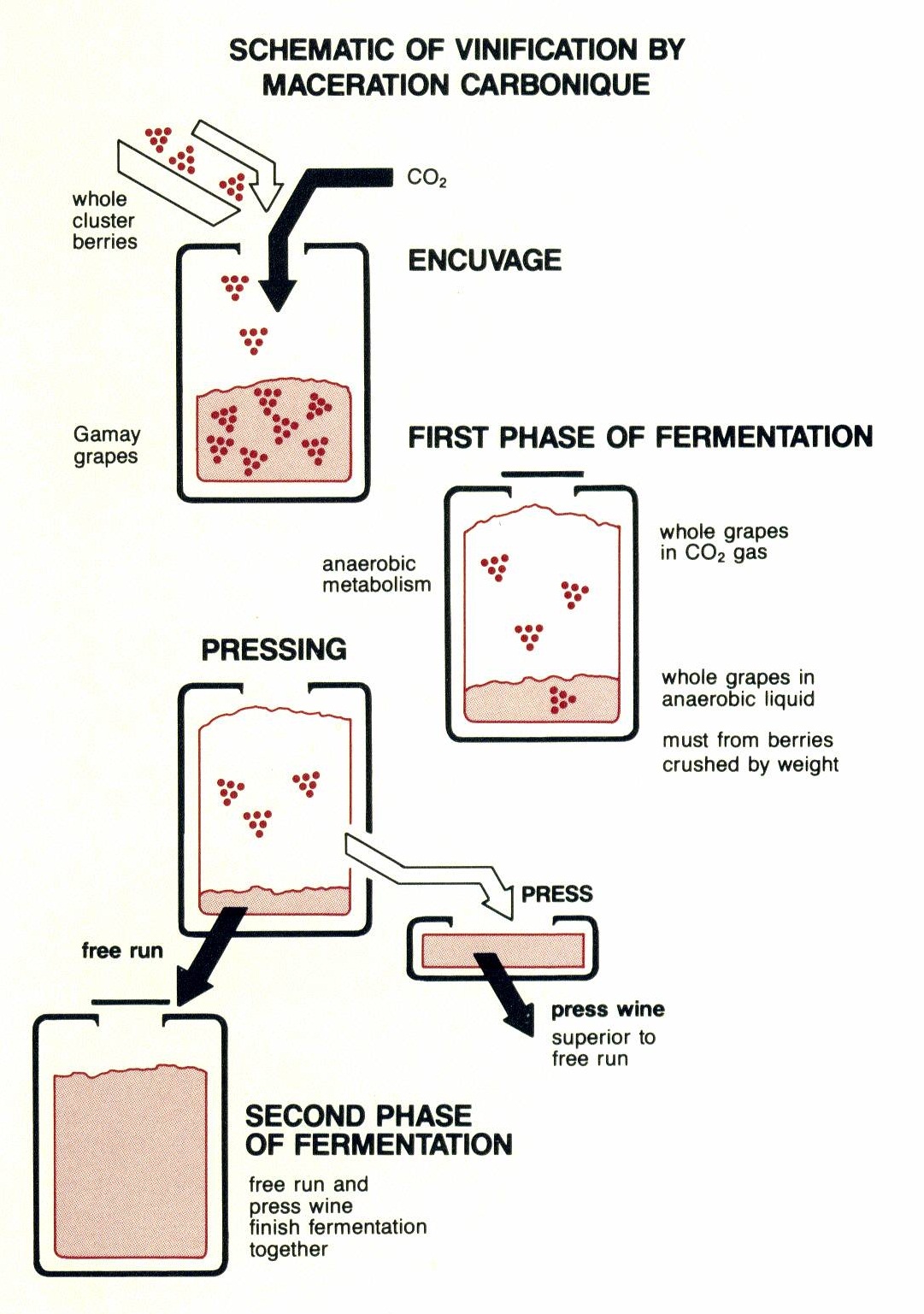

In carbonic maceration, on the other hand, there is no initial crush. Instead, entire bunches of unbroken grapes go into a vat that has been flushed with carbon dioxide and then sealed. Then the magic happens: the whole grapes take up the CO2 and a fermentation independent of any yeast involvement begins within the cells of the intact berries. In the process, the compounds that give wine color, flavor, and aroma move from the skins into the juice of the pulp, which turns pink.

To effect a full-on carbonic maceration, the winemaker will now remove the still unbroken grapes from the fermenting tank, draw off any free-run juice and press everything else. The resulting low very alcohol juice (no more than about 2%) is set aside to finish its alcoholic fermentation in a conventional way (Thanks to C.F. Shaw and Oerther Vineyard for diagram above).

Claude-Vincent Geoffray of Château Thivin in the Beaujolais describes the partially fermented juice as “very coloured, very perfumed, very fruity with lots of sugar and some alcohol. The Beaujolais call it paradis.”* I’d love to taste it, wouldn’t you?

For various practical reasons, the kind of full-on carbonic maceration I’ve described is less frequently found than some sort of part carbonic/part conventional technique. For example, intact berries may be left in the vat until they completely break down, inviting whatever yeasts are present (or are introduced) to initiate and carry through with a conventional fermentation. It’s this combination approach – or one of many permutations of it -that is most typical in the Beaujolais.

In either case, there’s nothing especially high-tech about the process. In this case, all those syllables don’t point to some sort of suspicious manipulation. The technique is sometimes referred to as ‘whole berry fermentation.’

Wine made via carbonic techniques will usually tip their hand by way of lower levels of tannin and acidity, and brighter (though often less deep) colors. A distinctive and lively set of aromas is typically present (more on this below).

One reason CM has been traditional in the Beaujolais is that the large amounts of malic acid consumed during CM means a malolactic fermentation (by which sharpish malic acid is converted to softer lactic acid) can be dispensed with, making it possible to ship a palatable wine within weeks, rather than months, of the harvest. CM is not used, so far as I know, in the making of white wine.

As for those carbonic aromatics, I have to admit that I struggle for a way to describe them. I can say that there is often a note of something that I call (for want of a better term) ‘gassy’ in the nose often accompanied by quite pretty strawberry, raspberry, cherry and, yes, even banana notes. Whether you can articulate it or not, it’s an aromatic profile that once experienced isn’t easily forgotten.

*Thanks to Sally Easton, MW for this quote, excerpted from her remarkable wine blog Wine Wisdom.