A chat with Julia Hallman, general manager at Formaggio Kitchen Cambridge this week about the shelf talkers that I had been busy rewriting. The time between taking the old ones down and putting the new ones up gave me a chance to see what the response of our clientele would be to their temporary disappearance. The result of our little experiment: shoppers really do rely on them.

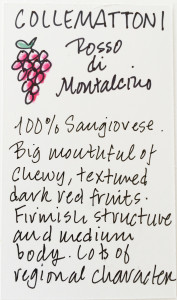

So now the question becomes what these signlets should say. There ‘s not a lot of space to work on business card size tags (example at left). Julia noted that based on what she had been hearing constituent grape variety/varieties are the most sought-after data. This started me down a road I’ve trudged before: just what is it consumers are thinking when they ask “What kind of wine is this?”

‘s not a lot of space to work on business card size tags (example at left). Julia noted that based on what she had been hearing constituent grape variety/varieties are the most sought-after data. This started me down a road I’ve trudged before: just what is it consumers are thinking when they ask “What kind of wine is this?”

It’s a question that has its origin in what I have called elsewhere the fog of wine: that disturbing combine of mystery, doubt, and anxiety all of us feel at one time or another as we try to find our way through the thickets of place names, soil types, cultivars, and flavor profiles wine confronts us with.

Though it seems natural enough now, clearing the fog by focusing on grape varietals is a relatively recent phenomenon. The likely reason it took so long: the wine industry’s deep, historic aversion to transparency. For centuries wine was distributed via brokers and negociants whose business it was to blend stocks of wine into saleable condition while completely obscuring the process by which they accomplished this.

Tavern keepers and householders would order Hermitage, or Medoc, or Nuits Saint-Georges and who knows what would actually be in the wine. It was very unlikely that end-users knew the names of the constituent varietals or, if they did, that they would have considered such information important.This knowledge was professional domain expertise restricted to people in the trade, the growers themselves, and few others. More likely they identified wine simply by its brand name — the Pommeroy’s Ordinary Claret of John Mortimer’s Rumpole stories.

Such was the case until at least the mid 19th century when it began to be chic for civilians to acquire this kind of insider information in the process of cultivating connoisseurship. So far as I know, the pervasive habit of identifying wine primarily by reference to its varietal composition is a mid-20th century phenomenon that took hold when the American wine, food, and travel writer Frank Schoonmaker had a hunch that that U.S. consumers eager for a firmer handhold on wine would latch onto this new approach as drowning sailors to driftwood. They did.

What are consumers thinking when they ask “What kind of wine is this?

Before getting too down on old Schoonmaker, recall that at the time he championed the technique at California wineries Wente and Almaden (where he was taken on as a marketing consultant), these properties and others in the Golden State typically sold wine under generic brand names such as Rhine, Mountain Chablis, and Hearty Burgundy. It mattered not all that wines so described bore no resemblance to the historic European regions their names evoked. Under the circumstances, Schoonmaker’s innovation has to be considered an advance.

In the 1980’s varietal labeling went mainstream with the appearance of a new kind of wine. Sourced mainly in California, Australia, and Chile these new products married low-price (well under $10) with a substantial rise in quality (the retail analogue might be IKEA or Target) and made chardonnay, merlot, and pinot noir as familiar to casual wine drinkers as red, white, and rosé. They’ve been known as “fighting varietals” ever since.

The curious thing about this identification business is how persistently wine buyers will find a single criterion a sufficient basis for deciding what to plunk down their money for.

It might be the varietal – but it might just as reasonably be a region, points awarded by critics, auction prices, cult status, or what is known to be trending at the moment: natural, orange, no-sulfur, oxidized, high-acid (remember the marketing for the Summer of Riesling? ), mountain-bred, small-producer, folkloric, wines vinified subject to cosmic influences, unfiltered, vegan, those having a touching story, the personality-driven (Look, a wine by Arianna Occhipinti!), wines with small mammals on the label – one could go on.

In light of this it becomes a real challenge to surmise what may be the single bit of information on a business card-sized tag that will prompt a shopper to reach for the Capital One card.

Maybe what we really need isn’t a shelf talker — it’s a fog horn.

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com

Follow Stephen Meuse