THE SKETCH AT LEFT is a bit of graffiti scratched by a first century Roman who may have been keen to have some fun caricaturing then Emperor Nero – as some think – or just engaging in an impromptu bit of self-portraiture. It’s sure the wag never imagined it would still be amusing people twenty centuries on, but there it is.

I was tickled by another piece of toilet stall humor from antiquity recently, a ditty that runs this way: Whoever wish to serve themselves can go get a drink from the sea. It looks to have been penned by some sassy barmaid wary of being deprived of the chance to provide the service that was the source of her tips, but there may be another layer or two in it worth peeling back.

Viewed from the perspective of our casual, self-service culture, it’s hard to imagine how thoroughly ritualized drinking was in the ancient world. In Plato’s Athens, among polite company, you didn’t either help yourself or drink freely. Wine drinking didn’t happen at the family table, it was reserved for post-prandial events in places set apart for the purpose where respectable women either weren’t present or weren’t respectable.

The formal drinking party – known as a symposion – involved games, word-play, spontaneous poetry, competitive oratory, philosophical banter, music, and other (frequently sexual) diversions. But among the horseplay and dallying its guiding principle was never lost sight of: drinking must proceed at a stately pace, with every guest draining his cup in turn during a series of rounds that were served out and from which no one could excuse himself. You might describe it as an orderly, supervised, progressive, communal descent into inebriation. It was also competitive. To be capable of a witticism or a song when your fellows no longer had legs under them, was to wobble off with the laurels.

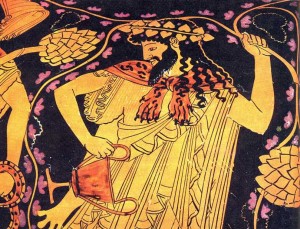

To this end, every symposion had its moderator whose first responsibility was to decree the proportion in which wine would be mixed with water in a great bowl called a krater, thereby fixing the amount of alcohol consumed in each round. Tradition held that it was Dionysus, the wine god, who taught men to mix water and wine in rational proportion.

We think of Dionysus as a bringer of disorder, so it’s strange to think of him as a moderating influence. But from the Greek point of view his stature as the giver of the gift of wine was only enhanced by his tuition in how to enjoy it while reinforcing, rather than fracturing, the social order.

Only barbarians (Thracians; Scythians) and the gods themselves took their wine straight up and imbibed it at will in a headlong dash to oblivion. By contrast, the Greek journey from sobriety to sublime wastedness was made via the medium of water and wine combined in ratios (1:2, 3:2, 4:3, 5:3) that recall the harmonic theories of fifth century BCE mathematician Pythagoras. To drink wine as it came from nature – unadulterated, we might say – was considered beastly. To adjust wine until it was in a condition that suited the occasion, the company, and the mood was (from the Greek point of view at least) urbane, civilized, social and– above all — human.

It’s curious that it was those emulators of all things Greek, the Romans, who eventually eroded both the communal and ritualized aspects of wine drinking and the habit of mixing. Early on they redefined wine as an ordinary accompaniment to meals (Hugh Johnson contends this took place at around the same time Romans became bread rather than porridge eaters and sees a relationship: Bread begged for wine). The Roman counterpart to the symposion known as a convivium, never quite became the deeply-rooted cultural marker it had been among Greeks elites.

Finally, as Rome’s legionnaires gradually shifted viticulture’s center of gravity deep into the river valleys of northern Europe a new kind of wine was born. Brisk, dry, austere, and lower in alcohol than the opulent wines of the southern and eastern Mediterranean littoral, these needed no water to either cut their richness or retard their inebriating effects.

As for self-service, we seem now to have totally bought into barbarity. At home we put a carafe or bottle on the table with the cheery encouragement to “help yourselves!” Same with most, but not all restaurants. I remember vividly a 1997 dinner at La Verriere, Eric Frechon’s first restaurant in Paris’ 19th arrondissement (he earned a third Michelin star at Le Bristol in 2009) when I was schooled on the subject by a young waiter.

Frechon’s place was little more than a homey neighborhood boite and the night we visit a single server is gamely working the entire dining room. He does his best, but can’t get around to every table with much frequency. Our glasses are empty and we long for a another pour. I hesitate before starting, timidly, to serve out some refills when the waiter comes flying over, whips the bottle out of my hand and says something in slangy French I don’t get, but now recognize to have been something very close to this: Whoever wish to serve themselves can go get a drink from the sea.