VINTNERS WITH PROPERTY in the steep hillsides that overlook the Mosel River between Trier and Koblenz have a worldwide market for their cooly aromatic, austerely-structured white wines. Today, growers there can count on steady demand and good prices. In the U.S., the hipster segment appears to have succumbed to the taut allure of cool-climate riesling – a trend sure to boost the Mosel’s fortunes in a demographic every winemaker in the world would love to capture.

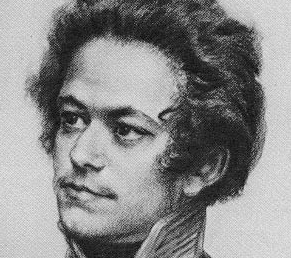

The road to success in the Mosel hasn’t always been paved with euros, however. For most of the nineteenth century the region was trapped in a vicious cycle of low regard, weak demand, and depressed prices. For the 24 year-old Karl Marx, a native of Trier whose family owned several vineyards, the source of the Mosel’s winegrower’s misery was directly traceable to inequitable political, economic, and class structures — a condition that could be overcome, in his mind, only by dismantling the present order and and putting something distinctly more progressive in its place. For Ludwig Gall, Marx’s older contemporary (and no mean socialist theorizer in his own right) the escape route took a more practical turn: making better wine. We’ll save Gall’s story for another post – it deserves separate treatment.

Modernization in German winemaking technique before the 1790’s had largely come via the leadership of its well-capitalized monasteries. With the French annexation of the Rhineland in 1794, religious houses were closed, their assets confiscated by the revolutionary government. Thereafter vineyard improvements – including replanting with the high-quality riesling vine – became a matter of state interest. But while wealthy landowners and prosperous bourgeois might have had the wherewithal to adopt new approaches, small holders clearly did not.

Marx’s efforts to bring the plight of the Mosel vintners to the public’s attention had a three-fold thrust, one that would later be familiar to readers of Das Kapital.

When the Rhineland returned to German control in 1814 following the defeat of Napoleon, the Mosel Valley was put under the authority of the kingdom of Prussia – an administration with no experience in winemaking, but one that knew its own interests and looked after them. They not only heavily taxed wine imported from foreign states, but from non-Prussian controlled regions of Germany. This gave the Mosel winemakers a substantial price advantage in some of the biggest northern cities. By 1818 prices paid to growers in the Mosel were higher than in any time in memory. But the good times didn’t roll for long. In 1828 Prussia abruptly removed tariffs for all German-made wine. Winemakers who had stretched to invest in additional or more valuable vineyard property under the old rules found themselves out on a very slender limb.

By 1842, when Marx became the editor of the Rheinische Zeitung, a start-up newspaper dedicated to supporting liberal, reformist causes, conditions in the Mosel Valley (the population was almost totally dependent on the vine for its economic well-being) had become desperate. Marx was fresh from university where he had been an enthusiastic follower of the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Hegel — but his agile mind had already turned away from the airy idealism that characterized German philosophical speculation of the period to concentrate his attention on the actual, material facts of life.

“Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways,” he would write a few years later. “The point is to change it.”

Marx’s efforts to bring the plight of the Mosel vintners to the public’s attention had a threefold thrust, one that would become familiar to readers of his Das Kapital: (1) a scrupulously detailed analysis of conditions on the ground with supporting data; (2) a withering critique of the political conditions that made redress via conventional means impossible; (3) the suggestion that powerful social forces in the form of class struggle endowed what was otherwise a purely local grievance with world-historical significance.

A series of articles on the subject appeared in the Rheinische Zeitung under the young editor’s name on January 15, 17, 18, 19, and 20 of 1842. Marx forcefully identified the main obstacles to alleviating miserable conditions in the Mosel as the Prussian state’s censorship of news information about the dispute, and a not-so-secret conviction on the part of the administration that the winemakers had only themselves to blame for their condition.

Does the state have the right to demand that families whose livelihood has for generations been based on viticulture turn to growing potatoes as the price of continued survival?

Marx allows that fewer properties making better quality wine would likely improve the situation, tax or no tax, but does the state have the right to demand that families whose livelihood has for generations been based on viticulture turn to growing potatoes as the price of continued physical survival? Does any administration have the right to demand its citizens to arrange their lives in such a way so as to adapt to whatever institutions are presently in place in order to co-exist with them – to demand that a population “transform its customs, its rights, its kind of work and its property ownership to suit the administration”? Vine-growers, he argued, were “deeply pained by such proposals.”

A more appropriate and humane relationship would be one in which “the individual carries out the work which nature and custom have ordained for him [while] the state creates conditions for him in which he can grow, prosper, and live.” According to his longtime collaborator Friedrich Engels, it was the Mosel controversy that led Marx “from pure politics to economic relationships and so to socialism.”

In his 1940 book on the intellectual sources of the Russian Revolution, To the Finland Station, Edmund Wison notes that when at the end of 1842 the Rheinische Zeitung was suppressed and its firebrand editor thrown out of work it had less to do with the controversy over the Mosel winegrowers than with some slanderous comments made by a rival newspaper which accused it of having communist tendencies.

“Karl Marx knew very little about communism,” Wilson reports, “but he decided to study the subject forthwith.”