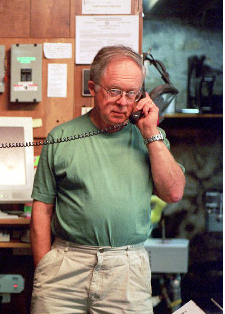

“Fine wine wine on a small scale” is how Kip Kumler (left) owner/winemaker at Turtle Creek Winery in Lincoln, Massachusetts describes his operation. The 900 cases produced there certainly fit the ‘small scale’ description. And anyone who has tasted some of Kip’s better efforts knows that the ‘fine wine’ part is also completely legit.

“Fine wine wine on a small scale” is how Kip Kumler (left) owner/winemaker at Turtle Creek Winery in Lincoln, Massachusetts describes his operation. The 900 cases produced there certainly fit the ‘small scale’ description. And anyone who has tasted some of Kip’s better efforts knows that the ‘fine wine’ part is also completely legit.

The term current in the wine world for people like Kip is garagiste (“gah-rah-ZHEEST,” roughly), meaning types who make fine wine on a (typically very) small scale. Only the passion is outsized.

Kip makes wine from grapes grown on his property as well as from fruit he purchases from other growers — some outside New England — and he gets around. He’s active in the Massachusetts Farm Winery movement and likes to throw his wines into comparative tastings here and elsewhere.

We were chatting by email with Kip while working on a column about New England wines this past week and asked about the grapes in his 2010 Massachusetts chardonnay. He volunteered that the fruit is not from his Turtle Creek property, but from another Mass vineyard and that he had blended in a small percentage of California fruit, too.

This piqued our interest. When we queried him on his use of West Coast fruit, he replied as follows:

“It’s part of a series of experiments to explore the symmetry between East & West grapes. In the West, the practice is to add acid, sugar [being a] non-issue. Here, in the East, the practice is to add sugar, acid [being a] non-issue. Therefore, instead of adding refined sucrose or refined tartaric acid, why not add the complementary fruit and, as a dividend, get possible complexity, as well?”

He went on: “I am the first to acknowledge that this idea is a non-starter for marketing programs or for terroir ideologues, but, from a technical POV, it is interesting.”

We agreed the idea is interesting. After all, winemakers are always blending different lots in an attempt to tune wines a bit, or compensate for perceived deficiencies.

Sometimes this means blending different lots of the same varietal, or from the same designated region – sometimes not. The technique has been known and practiced forever.

By terroir ideologues, Kip means individuals who believe it is above all a wine’s job to express a sense of the place it came from. Naturally, the “whereness” of a wine fades when its components don’t share a source. For these purists (a little word play on the French term turns them into terroiristes) blending New England and California grapes is not quite the thing.

To illustrate how unwelcome his East-West experiments can be among persons of this persuasion, he recounted the following:

“I was at a wine tasting among winemakers in the ———- region last year. The ostensible purpose of the tasting was to see if we could discern a “sense of place” among the wines presented. In my opinion, this was difficult because most of the wines had remedial problems. Most of the winemakers acknowledged this and concentrated on discussing what to blend ————– chardonnay with: riesling, traminette, etc. I do not know whether our own chardonnay offered any sense of place but it was clearly the best chardonnay among the flights and everyone thought so until I explained what I had done. After that, I felt I was persona non grata.”

Terroiriste or pragmatiste? The question comes down to whether your highest purpose is to make a regionally typical wine . . . or just a delicious one.

File under: Can’t we just all get along?

Originally posted on Boston.com