When the exotic beverage known as coffee first appeared in Europe in the second half of the seventeenth century, inns, taverns, alehouses, pubs and caterers of every description were already well-entrenched.

There were plenty of places to get a drink, a meal or a snack, although the restaurant as a place offering a menu of single-serve, cooked dishes you could order from a printed menu at almost any hour and consume at your own table in an on-premise dining room was yet to be invented. Early coffee houses were noisy, even raucous places where men (it was men only at that point) could meet, read newspapers and argue equably about politics and conduct business. Initially, food doesn’t seem to have been part of the picture.

It’s hard to know exactly why, when new riffs on these institutions appeared in the late eighteenth century, they became known as cafés*, since they had evolved well beyond coffee service. Historians of sociability describe these spots as emerging to serve the needs of a growing urban population of laborers, bureaucrats, shop clerks and office workers. Within a hundred years, Paris alone had 42,000 cafés, or about 11 per thousand inhabitants — a world record at the time.

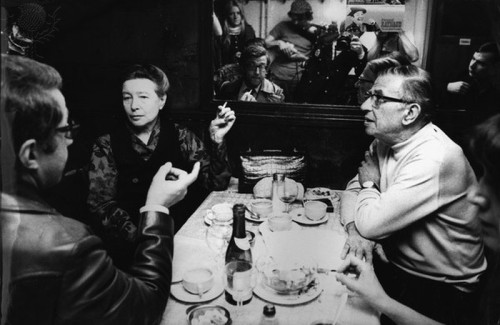

The café has many romantic associations — just think of Sartre and Beauvoir at Les Deux Magots, above — but none more delightful than the ones you yourself bring home from visits to European cities like Paris, Milan, Madrid or Budapest (where the café life is pretty much life itself) or from the simple neighborhood mom and pops that are responsible for the much of the charm (if there’s any to be found) in thousands of obscure villages and townships. If you even once enjoyed some modest regional dish, competently prepared and served by a welcoming host at such a spot, you never forget it.

In the wine corner, you’ll sometimes hear us talk about café-level wine as if it were a recognized category. It’s not, really, but it should be.

For us, café-level describes wine that is at once serviceable, drinkable, economical and pleasurable. Serviceable, meaning that it has the soundness and character to do what is asked of it. Drinkable, because in this context a proper wine is like a good story that gets on with it and doesn’t encumber the narrative with big words or challenging sentence structure.

Because these wines are typically served alongside modestly-priced dishes, it is essential that they are likewise affordable, and served in ways that are tuned to individual taste and capacity. It’s a rarity today, but I remember enjoying the sight of a single bottle making its way around a tiny dining room, a knotted string dangling inside the neck marking how much each table had consumed and thus ensuring the accuracy of l’addition.

One does still routinely see wine brought to the café table in a sturdy carafe or jug (in Palermo, it might be the ancient cucumela) containing a half or even a quarter bottle.

As for the pleasurable part, let’s just say that in this respect, café wine makes its contribution as part of a team — playing its role; doing its job. Not drawing attention to itself, but doing its best to make the whole meal sing, and, in its own way, memorable.

It goes without saying that wines of this stripe make ideal weeknight sips, and are perfect for laying in a small stock to serve as house wines. At home, we enjoy mixing it up bit. That way, from night to night, we get to revisit some of the little towns and cafés that welcomed us in our travels over the years, without ever leaving home.

Tonight Toulouse; tomorrow Salamanca.

*One might ask the same question about school lunch rooms in America which became known as cafeterias.