The Georgians – and here I refer to those denizens of the Caucasus Mountains rather than the inhabitants of the sprawling suburbs of Atlanta — claim to be on vintage no. 8000, or thereabouts. If true, their boast sets the origin of wine culture deep into the era we call the neolithic and makes wine older than cities, writing, and metallurgy.

It’s amazing all right, but not quite as amazing as it would have appeared to a pious Anglican of the 17th century who, on the basis of a chronology worked out by Bishop James Ussher, was convinced that the creation of the world had taken place as recently as October of the year 4004 BCE. Under Ussher’s scheme, wine would be even older than the earth.

Okay, so the bishop of Armagh was way off. But even if we just stick to what the Bible has to say on the subject, wine appears as one of man’s early and important achievements. In the well-known story of the great flood that appears in Genesis chapters 6-9 we’re told that the first thing the patriarch Noah did after emerging from the ark with his family was to plant a vineyard.

We can skip over the question of where Noah got the plant material to establish his new property, since it’s clear that getting too literal isn’t likely to lead anywhere. The more interesting question goes something like this: why would a man who had just come through this epic, traumatic ordeal choose as his first post-diluvian project one that requires daunting amounts of labor and offers no immediate reward? After what he’d seen, what assurance did Noah have that God’s wrath wouldn’t be visited on the world again, perhaps this time wiping out all life, no exceptions granted?

We get the answer a little later in the narrative: And I will establish my covenant with you; neither shall all flesh be cut off any more by the waters of a flood; neither shall there any more be a flood to destroy the earth. And God said, This is the token of the covenant which I make between me and you and every living creature that is with you, for perpetual generations: I do set my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a token of a covenant between me and the earth. The rainbow was Noah’s guarantee that his labor wouldn’t be in vain.

Some theologians see the Noah story as the original creation story (Adam and Eve and all that) recast in terms of de-creation and re-creation. Viewed this way, Noah’s vineyard is a kind of Garden of Eden do-over. And if the site of the world’s fresh start is a vineyard, is it any wonder that what naturally issues from it – namely, wine – should thereafter play a leading role in Jewish and Christian scriptures, ritual, and symbolism?

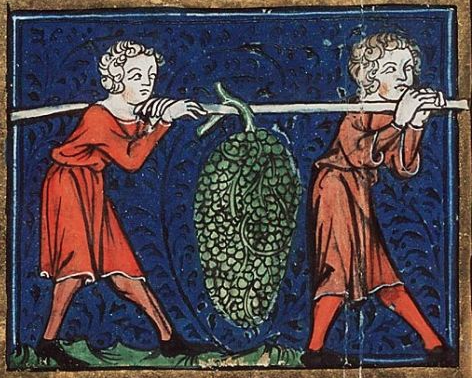

A lightning-round recap: Moses encourages the people in their Exodus wanderings by reminding them that the promised land not only flows with milk and honey, but is rich in vineyards. The scouts Joshua and Caleb, sent on a mission to reconnoiter the unmapped area, return with a giant cluster of grapes as proof that the land overflows with wine. The unmistakeable message: the whole territory is Edenic.

Jesus describes himself as the true vine and his disciples as laborers in his vineyard. At the Last Supper he tells them to drink wine in commemoration of his redemptive death. The mass — Catholic, Anglican, and Orthodox — cannot be celebrated without the fermented juice of the grape. Four cups of wine drunk at the Passover seder represent release of the Jewish people from their four periods of exile. How will we know when the millennial kingdom that both Jews and Christians anticipate has come? Because in that day “new wine will drip from the mountains and flow from all the hills” and “every man will sit under his own vine and fig tree.”

In the northern hemisphere, Easter and Passover come around each year just as vines are emerging from their annual slumber, and showing the first promising signs of a harvest to come. It’s a time when the world seems to be starting fresh, and there’s a sense of futurity in the newness of it all. In New England, more dramatically than elsewhere, April brings a kind of Noah moment for each of us as we contemplate a vegetative world that had been de-created by winter newly restored to verdant life.

Not all of us can share Noah’s joy in planting and tending a vineyard of our own, but we can each enjoy the scent of paradise that still clings to wine – even after 8000 vintages.

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com

Follow Stephen Meuse