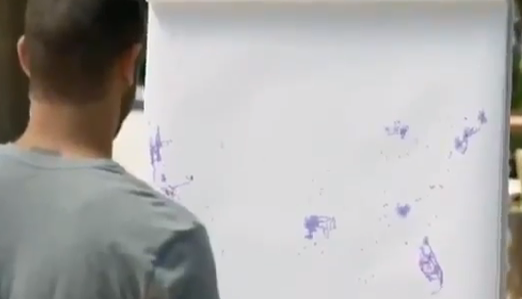

By now it’s likely you’ve seen one of the new spots Verizon has rolled out touting the reach of their nationwide wireless network. In the ads people are set in front of an easel spattered with colored dots, each representing a unit of network coverage for a particular carrier and asked to identify what they see. The sketchy coverage of a competitor’s network, above, doesn’t provide enough information to give this person an idea of what he might be looking at, but when the dottier Verizon coverage is represented the same way, below, the familiar shape of the continental U.S. emerges.

By now it’s likely you’ve seen one of the new spots Verizon has rolled out touting the reach of their nationwide wireless network. In the ads people are set in front of an easel spattered with colored dots, each representing a unit of network coverage for a particular carrier and asked to identify what they see. The sketchy coverage of a competitor’s network, above, doesn’t provide enough information to give this person an idea of what he might be looking at, but when the dottier Verizon coverage is represented the same way, below, the familiar shape of the continental U.S. emerges.

Apparently vision isn’t enough to be able to navigate the world and act purposefully in it. Visual inputs have to be processed somehow before it becomes possible to distinguish a friendly face from a threatening one, or to recognize a family member. The brain’s ability to store visual images in memory and more or less instantly compare them with new inputs for similarities and dissimilarities is impressive.

Rather than deal with the many individual features each of these memories contain, we find it more efficient to stitch the bits together into patterns that we can more quickly retrieve and apply to recognition problems. The shape of the continental U.S. is one of these patterns.

A rather newer idea is that this is exactly what happens with sensations of taste and smell, too. In both each case the brain receives sensations and works them over, constructing a composite “image” of the experience. The operational similarities involved in the formation of visual, taste, and olfactory perceptions are so similar that one neuroscientist has referred to these composite inputs as “flavor images.” * Like visual images, flavor images can be retrieved for comparison purposes when we’re confronted with something new.

When a flavor image is retrieved it surfaces trailing all the circumstantial and emotional baggage it was packed away with.

But it’s not just the tastes and smells of what we ate and drank that gets filed away, it’s whatever else happens to be going on around us at the time: including what we were watching or hearing, whose company we were in, and whether we were feeling safe and happy or vulnerable and anxious. And when a flavor image is retrieved it surfaces trailing all the circumstantial and emotional baggage it was packed away with.

The most celebrated example of this is surely the one provided by French novelist Marcel Proust for whom “the whole village of Combray and its surroundings, taking shape and solidarity, sprang into being, town and gardens alike” as he nibbled the now famous tea-soaked madeleine. Anton Ego’s nostalgia scene in the Pixar film Ratatouille makes the same point in a scant, exhilarating 45 seconds.

One bite of chef Linguini’s confit bayaldi (a posher version of the homey, classic dish known as ratatouille) and the lonely, self-absorbed critic, above, is vaulted back to childhood. (Click on the image to view the clip).

When professional wine tasters ply their trade, they rely on their memories and techniques of pattern-recognition to make judgments about varietal character, winemaking technique, and conformity to a standard – among other things. Where there are blanks spaces they sketch them in provisionally until something recognizable emerges.

If tasting is a professional skill that can be learned and passed on, why don’t tasters of roughly equal experience agree more often than they do? How is it that they can be thrown wildly off track when, as some experiments have shown, wine is mislabeled or mispriced, or when white wines are disguised as reds?

My guess is that they would agree more and be mistaken less if only the brain operated a little differently than it does and we could bring up just the information and leave the affect behind. It just doesn’t seem to work that way.

On the other hand, it’s worth noting that for Ego, his quick trip via confit bayaldi to the kitchen of his boyhood home doesn’t cloud or disable his critical faculties; it humanizes them.

In a post a few weeks ago I noted that “. . . it’s very often circumstantial factors (food, company, mood, time of day) rather than something inherent in the wine that leaves you thrilled or disappointed with it.” Now I think I know better why.

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com

Follow Stephen Meuse

*The concept of the “flavor image” is proposed by Dr. Gordon M. Shepherd of the Yale School of Medicine in his 2012 book Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why It Matters.