The twentieth may have been the American century, but it was during the eighteenth that we made the transition from an ethnically uniform but marginally viable colony of the British Empire clinging tenaciously to the east coast of North America to a fully independent administration taking its place and its chances among the nations of the world.

The Declaration of Independence is still a thrill to read 238 years after its composition by a youthful Thomas Jefferson under the watchful eyes of Benjamin Franklin and John Adams.

It’s not clear how or on what timetable the declaration was actually read or heard by citizens of the spanking new United States of America, but if you were a partisan of independence it must have rejoiced your heart to read such a stirring defense of your cause and driven you to raise a glass to its prospects. But what would that glass have held?

Let’s survey the possibilities …

Cider. Hard cider was a staple drink wherever the apple tree could be induced to fruit – and that was much of North America. According to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, fermented apple juice was colonial America’s “foremost beverage and remained so well into the nineteenth century.” Without further elaboration apple cider could attain alcohols of no more than about 6%, but freezing or boiling the juice would concentrate the sugars and result in the more potent drink known as applejack. An infusion of rum could be added to achieve the same purpose. Cider was rural America’s daily drink.

Beer and Ale. One reason the Mayflower landed at Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620 and not at “Hudson’s River” (the original destination) was because they were running low on stores of beer and there was fear that if they went further there wouldn’t be enough left for the ship’s crew to make the return voyage. With no barley at hand the pilgrim community struggled to make beer with whatever grain that could be had, including Indian corn (maize). The first licensed brewery in Boston was established in Charleston in 1637.

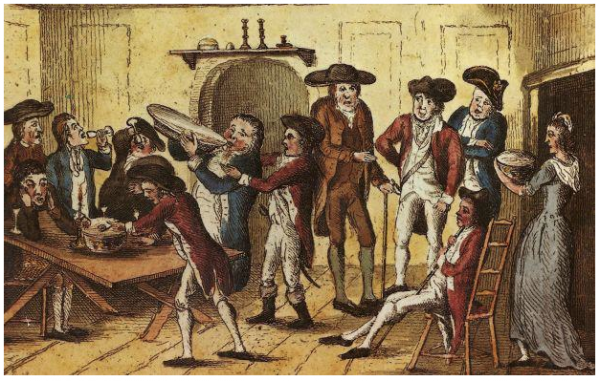

By the 1660’s there was a sufficient number of breweries to require legislation establishing minimum quality standards. In the years leading up and during to the revolution taverns where beer and ale were served abounded and assumed importance as places where groups met to discuss grievances and strategy, in some cases serving as nurseries for what would become state government. In 1787, on the last day of deliberations by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, General Washington made this note in his diary: The business being closed, the members adjourned to the City Tavern. Beer was, as it is today, the sociable drink of masses of Anglo-American males.

Whiskey. Emigrants with Scottish or Irish roots arrived in the American colonies with a taste for this distilled spirit and a talent for making it (or maybe it’s the other way around). Scots-Irish immigration rose mightily in the 1730’s and so did the number of stills, but New England wasn’t the best place for growing wheat or rye. Better soils for these grains (and corn) were found further west, in Pennsylvania and Virginia. Washington maintained a distillery on his estate at Mt. Vernon where, in 1799, he produced 11,000 gallons of whiskey.

One powerful motivation for making whiskey in early America was provided by the bad condition of roads and consequent high costs of transport: distilling condensed many barrels of grain into a single barrel of fiery spirit. When the young republic attempted to raise cash to pay off its revolutionary war debt by taxing whiskey and bourbon in 1791, it found itself with a full-scale rebellion of its own on its hands. From the beginning whiskey seems to have been a drink of the frontier rather than of the young republic’s more well-established communities.

Rum. Distilled directly from sugar or from molasses, a by-product of sugar refining, rum was for a while the most popular and widely available distilled spirit in the northeast colonies, though there would have been both a measure of poetic justice and no little irony involved in toasting independence with a cup of it. Justice, since British taxing of rum’s raw materials in the Molasses Act of 1733 and the Sugar Act of 1764 was a continuing cause of colonial vexation.

From the beginning whiskey seems to have been a drink of the frontier rather than of the young republic’s more well-established communities.

Irony, because rum production anchored one corner of the infamous triangle trade by which molasses shipped to New England from the Caribbean was processed into rum which was then exchanged on the West Coast of Africa for slaves. The human cargo was in turn shipped to the Caribbean for sale to planters who needed workers for the notoriously labor-intensive work of sugar manufacture – completing the vicious commercial polygon.

One wonders how a citizen of Boston could so so obtuse as to celebrate the declaration’s daring assertionthat all men are created equal, endowed by their creator with inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, with a tot of rum. Not much yo ho ho in that.

Punches. Early versions of what we would later refer to as cocktails were generally rum-based with fruit juice added. Punch was popular at mixed-sex gatherings where the drink was considered more genteel than beer or hard liquor.

Punches were inevitably social in nature. Men eager to establish a bond of solidarity passed the punch bowl around for all to drink from. Grog, the traditional beverage mixed and served out twice-daily to ordinary seaman in the British and American navies consisted of rum, water, and lime juice (to fend off scurvy), was a kind of punch. More menacing than a flogging, a threat to “stop your grog” was usually enough to return the surliest foretopman to his duty.

Wine. The vision of Jefferson sipping claret in the dining room of Monticello colors our view of wine in this period, but Jefferson was a wealthy man and had spent a significant time in France first as a diplomat and later as a tourist. His deep knowledge of and experience with French wine was atypical, however. For most of the eighteenth century, beginning with the war of the Spanish Secession in 1702 and carrying on until the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 Britain and its colonies were at war with France and so its subjects were periodically either cut off from the sources of French wine or forced to pay very high duties on its importation. As for local wines made from native U.S. grapes, that project had been a failure pretty much wherever it was tried.

The Methuen Treaty of 1704 brought the Portuguese into alliance with Britain against France with a promise that Portuguese wines would always be taxed at a rate lower than French wine. Reflecting on the event in 1824, Alexander Henderson wrote “By taxing any commodity excessively, the use of it will, no doubt, become confined to the wealthiest classes … and this may be said to have the case with the wines of France.”

The treaty gave a boost to the production of the powerful, fortified wines of the Douro known as Oporto or Port, which subsequently became a favorite of British drinkers. But British and British colonial consumers had long been keen on the sugary, high-alcohol wines produced in Spain in Portugal in part since they were more durable on long ocean voyages. The English delight in the wines of Jerez – sherry or sherris-sack) is documented as far back as Shakespeare’s time.

The powerful, durable, partially oxydized wines that had their origins on the island of Madeira (Portugal), the Canary Islands (Spain), and in Malaga on the Andalusian coast were robust, affordable alternatives to the products of French vineyards and in every year from 1696 to1785 imports of these wines dwarfed those of France.* In the colonies, European wine would have been a drink confined to the wealthy professional, merchant, or land-owning classes.

* * * *

In 1776 the neonatal nation as a whole had a wide variety of beverages to choose from in standing to offer a toast on what has become known as Independence Day, but any individual’s experience was likely to be severly circumscribed by any number of social, geographic, and economic factors.

So what should it be in 2014? Considering the crucial help the French gave our fledgling republic in the years from 1778 to 1783, and the fact that they bankrupted themselves doing it, I’ll be raising a glass of the best claret in my cellar – and damn the duty.

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com

*The History of Ancient and Modern Wines, Alexander Henderson, London, 1824. Appendix No. VIII “An Account of the Quantity of Wines Imported into England from Christmas 1696 to Christmas 1685; distinguishing the Quantity and Species of Wine imported in each Year.”