The impending (or perhaps only threatened) 100% tariffs on some European luxury goods has the wine industry in a tizzy – as well it might. As Jenny Lefcourt, an importer of natural wines outlined in a recent New York Times letter to the editor, the industry has a deep reach into American business and the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of workers and their families. Beyond the retailers, wholesalers and importers themselves there are, per Lefcourt, the many “office assistants, truck drivers, forklift operators, logistics coordinators, bookkeepers and restaurant chefs and servers” all of whom who could be in for some hard times.

Let’s all hope (and do what we can to see) that it doesn’t come to that. But if it does, it will hardly be the first time that governments in search of more revenue or a fresh hammer with which to beat their commercial rivals (or actual enemies) have turned to wine as a reliable instrument of both. The most vivid example provided by history is surely the enduringly contentious relationship between the English (later, British) and the French. So long as the English possessed a large swath of France’s southwest territory, its vineyards and the port of Bordeaux to boot (all part of the dowry Eleanor of Aquitaine brought to her marriage with the future Henry II in1152), the traffic in wine to English ports flourished, subject only to reasonable taxation.

Later, as the two kingdoms undertook generational war, wine and the revenue it begot became strategic assets. Since England was France’s richest market for its claret, any slowing of the flow of wine to its ports hit the French treasury hard. Raising tariffs was thus a favorite resort during times of tension. When hostilities flared into outright war, Old Blighty could, and generally did, ban imports of French wine tout court.

The results of either action were predictable: hardship all around as both producers and merchants suffered from the interruption in trade; an increase in the value and price of wine already landed; a boost for gray and black market activity; a drumbeat of complaint from consumers deprived of one of life’s sweet, innocent pleasures.

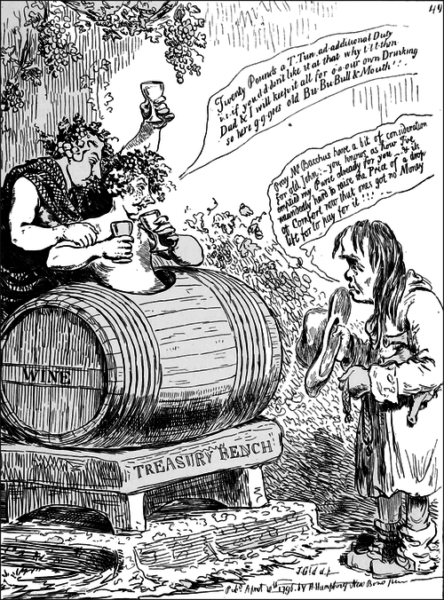

That’s James Gillray’s satirical drawing of 1796 (“Pray, Mr. Bacchus, have a bit of consideration for Old John”), above, depicting John Bull begging for a relaxation of the liquor tax created to fund the Pitt government’s struggles against the French revolutionary regime.

Wine used as an instrument of war – or even just policy — can have surprising, unintended effects. It was an English embargo of French wine in the 1690’s that created a market in England for the wines of Portugal and got a newly invented potation called Port off to a roaring start.

It’s not at all clear what effect this latest attempt to use wine as a weapon in international commercial conflict will have. But if history is any guide, we can be sure of one thing: Like the present administration, it can’t — and won’t — last.