Wine talk is surely as old as wine itself, or, if not quite, then at least as old as wine whose source could not be taken for granted by the person consuming it. The moment wine made the leap from something both created and consumed by the same household to an article of commerce, the services of someone capable of narrating its origins and character were required — and wine splainin’ was born.

Though at first, wine talk must have been just talk, it made a graceful transition to written form once that medium became available. Some of the first we know of appears on seals used to identify the contents of clay wine jars in ancient Egypt. By Tutankhamun’s time (13th c. BCE), wine seals might be nearly as detailed as modern labels.

A first century Roman compendium of natural history catalogued scores of contemporary wines along with detailed descriptions of how each tasted. The second century imperial physician Galen identified many wines by name along with their respective therapeutic uses.

The kind of wine writing we’re all familiar with has its origins in the early modern period when English brokers published lists of French wines (typically blended in their quayside Bordeaux cellars) available from them. Before the 18th century, innkeepers and well-to do consumers bought by the barrel and drew from cask for use at the table (English diarist Samuel Pepys purchased and served out wine this way). The bottle and cork revolution changed all that.

But it wasn’t until the early 19th century that works by disinterested authors (that is, not having a financial stake in the wine they talked about) appeared. André Julien’s Topographie de Tous les Vignobles Connus was a watershed in this genre, as was Cyrus Redding’s 1833 opus History and Description of Modern Wines.

Suddenly, detailed information about (mainly) French wine was available to anyone with an interest in the subject – no travel required. It was an American wine writer, Frank Schoonmaker, who in the 1940’s and 50’s popularized wine talk that focused on varietals rather than regions.

In 1978, a young attorney named Robert Parker Jr. began distribution of a modest newsletter. The Wine Advocate, with its 100 point rating scale, rapidly became the most influential wine publication in any language, ever.

A high Parker score sent the troops racing to the wine shop; a low score doomed a wine to oblivion. Today, points and tasting notes seem to be all a certain segment of the wine-consuming population is interested in – almost more so than the wine they purport to speak for.

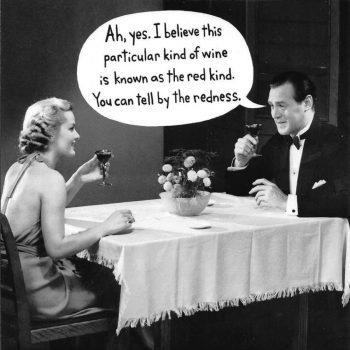

All this begs the question: Why can’t wine just ‘splain itself?