Winemaking is simple, but isn’t always easy. From the beginning, crafting sound, durable wine has been a challenging undertaking.

Winemaking is simple, but isn’t always easy. From the beginning, crafting sound, durable wine has been a challenging undertaking.

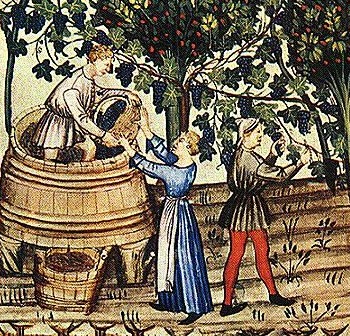

The medieval Church was exceptionally good at it because it had (i) heaps of money, (ii) swaths of prime vineyard land (thanks to the pious bequests of expiring nobles eager to endow masses for the repose of their souls), (iii) a literate leadership capable of keeping detailed records and institutionalizing knowledge, and (iv) many thousands of devoted rank and file monks to perform the laborious tasks of planting, pruning, harvesting and pressing.

It was important work for more than one reason. Wine was essential for the performance of Mass. Its sale paid the bills. Abbots knew that one couldn’t count on a series of accidents to make quality wine. Even in the hands of skilled vineyard managers and cellarmasters, It was a risky undertaking.

Today, it’s easy to think that making wine in a more natural way is just a matter of doing things in a non-technological, low-intervention way: the old way. There’s some truth in this, of course, but it’s only because modern science has made it safe to operate this way.

Before Pasteur’s experiments with milk, beer and wine in the 19th century disclosed a world of invisible and unsuspected living agents — unimaginably multitudinous swarms of microbial life — no one really knew why their Pinot Noir sometimes turned prematurely to vinegar or, though healthy when embarreled, was later found to be infected with unpleasant smells and flavors. It’s more than a little ironic that it’s our advanced knowledge of microbiology and the development for modern techniques to manage it that makes possible a return to what we might call pre-modern winemaking

In the wine corner we have no tolerance for additives — but a little dose of irony here and there is always welcome.