The first order of business for the Biblical patriarch Noah — once the ark came to rest on Mt. Ararat and he and the fam set their sandals down on dry land once again — was to plant a vineyard. We are not told where the vines for this enterprise may have come from, but as an article of faith one needn’t inquire into it too closely.

The first order of business for the Biblical patriarch Noah — once the ark came to rest on Mt. Ararat and he and the fam set their sandals down on dry land once again — was to plant a vineyard. We are not told where the vines for this enterprise may have come from, but as an article of faith one needn’t inquire into it too closely.

It is perhaps something of a weakness in Holy Writ that it raises so many more questions of this sort than it answers. To address this we invented DNA sequencing, where history — or at least the part that deals with biological evolution — leaves its fingerprints.

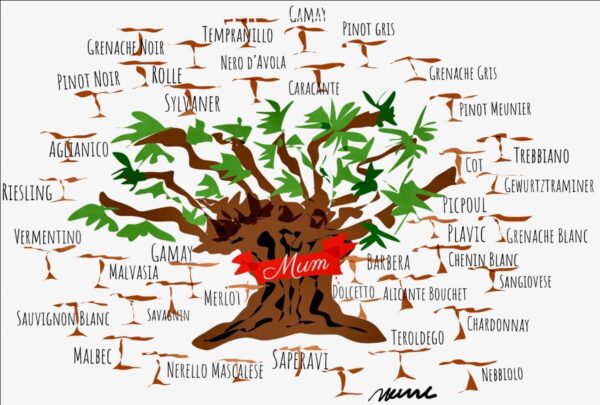

In the last two decades, amelography (as such research is known) has done much to clarify and organize the family tree of the wine vine — a large, extended and unruly clan with members hither and yon. From the perspective of wine drinkers, the situation seems much tamer than it really is, since most of us would struggle to get very much farther than Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay if asked to name as many wine grape varieties as we could think of.

While it’s true that this group dominates the commercial wine scene, in point of fact, something like a thousand varietals are regularly in use making wine today — though of this number many are obscure to the poinof constituting esoterica.

Why so many? There are two reasons, really. One is the vine’s sex habits, which one may not uncharitably describe as busy and undiscerning. The second is the altogether human way they pass along their genes. Like human children, wine vine offspring share some of the physical and temperamental characteristics of their parents, but are not perfect replicas. Mutations are frequent, some of which make a child vine more useful for the purposes we have for it; some less.

In theory, every new vine begotten via good, old-fashioned hooking up represents another distinct wine grape variety. The only way to ensure and enforce perfect varietal integrity is to short-circuit the dating scene altogether in favor of fully supervised, non-sexual reproduction. Known as cloning, it is unexciting but reliable.

The ultimate aim of all this genealogical sleuthing is to determine which, if any, among existing varietals can be identified as the parent of parents, the Mum of Mums. I regret to inform that, so far at least, the search has not, one might say, borne fruit. The best we have been able to do is identify some mildly surprising family connections.

Along these lines, The Oxford Companion to Wine mentions that Chardonnay appears to have emerged as a spontaneous cross between the red Pinot Noir and the white Gouais Blanc, and that the latter is known around research lab watercoolers as “the Casanova of grapes” as a tribute to its numerous vinous liaisons and success in scattering its chromosomal riches far and wide.

The best we can say for now — and probably ever — is that our dear old Ur-Mum, whoever and whatever she was, lives on in innumerable bits and bytes of bio-data scattered about in the great wide winosphere, that is to say (to some highly attenuated degree) in every bottle of supermarket plonk, every crystal decanter of first growth claret, and everything in-between.

So here’s to you, Mum. We owe you everything.