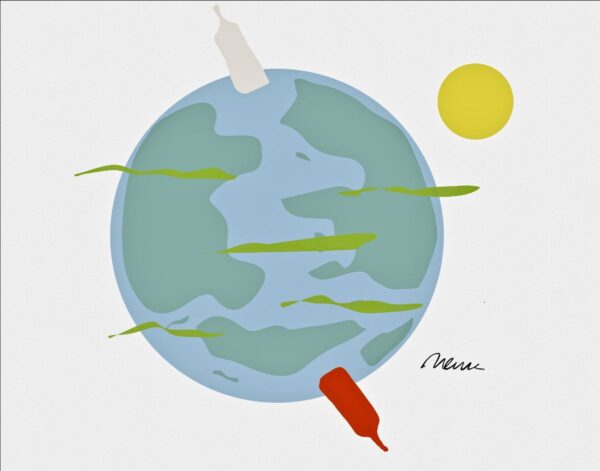

Red and white might as well be the north and south poles of wine, reliably serving as stable orientation hubs on the vast and often confusing surface of planet Vino. Wine shops, wine lists and wine books all tend to organize themselves around these binary reference stations. So pervasive is the white/red divide that we scarcely give a thought as to why we insist on conceptualizing wine via this rather confining scheme. It wasn’t always so.

We would have to go back a long way indeed have an idea of just when the mutation that gave us the white grape popped up (from what I’ve read, its the darker-hued fruit of the vitis vinifera vine that has the priority in terms of time). But this hardly mattered in the earliest days, since our ancestors were so delighted with the magical properties of yeast fermentation that they would throw anything into a pot that might result in the production of alcohol — vine or tree fruit, berry, honey, whatever.

Only very gradually did refinements set in and our promiscuous neolithic cocktail morph into a beverage made exclusively with grapes.

By the time we get to our old friend Pliny the Elder, and the section of his encyclopedic first century C.E. natural history that deals with the vine, red and white grapes and their resulting wines are clearly differentiated. But it would be a mistake to conclude from this that both colors were not frequently found growing together into the modern era (the old French phrase for this is en foule, ‘ in a mob’), being harvested and vinified into wine that made good use of what each had to contribute. Where such vineyards are found today, the technique is still practiced. We describe wines made this very traditional way as field blends.

This collusion of the red and the white isn’t confined to what we might call farm wine, however. A number of important, prestige appellations permit it. The traditional Champagne recipe, for example, calls for two red grapes (Pinot Noir and PInot Meunier) to be blended with Chardonnay. In the southern Rhône Valley, Châteauneuf du Pape rouge may include Grenache Blanc, Bourboulenc, Clairette and Roussanne; in the north the reds of l’Ermitage and Saint-Joseph permit modest amounts of Marsanne and Roussanne while in Côte Rôtie Viognier may be added. With some exceptions, 10% white fruit is permitted in Chianti.

Since mixing in a bit of white fruit serves to lighten and freshen wines made predominantly from red grapes, it may be that one way winemakers could mitigate the effects of global warming on their red wines (premature ripening; soaring alcohols) would be by relying a bit more on additions of white varietals, where permitted.

Meanwhile, both rosé and orange (skin-macerated white wines) are reaching wider audiences, underscoring the fact that white and the red have never quite been the perfect oppositional pair we’ve made them out to be — and highlighting a relationship that has always been and remains, shall we say, fluid.