ALMOST ANYONE who has ever had a frustrating conversation with an over-zealous sommelier or retail clerk knows that wine is bedeviled by jargon: the language peculiar to a given field that insiders use to recognize each other and keep the uninitiated at arm’s length.

ALMOST ANYONE who has ever had a frustrating conversation with an over-zealous sommelier or retail clerk knows that wine is bedeviled by jargon: the language peculiar to a given field that insiders use to recognize each other and keep the uninitiated at arm’s length.

I suppose I have to admit to being a wine insider, but as I work the floor at Formaggio Kitchen I remind myself how off-putting the use of jargon can be and do my best to avoid it. Often, my best isn’t good enough. I don’t always recognize jargon when I speak it.

Asked to describe a red wine, I might use ordinary words such as extraction, density, or concentration – only to be met by a blank stare. Such words seem plain enough, but somehow when the subject is wine they sow more confusion than clarity. My guess, reinforced by experience, is that people assume that when applied to wine these mundane terms take on arcane, specialist meanings — like a secret handshake — when in fact they mean pretty much what they do in any other context.

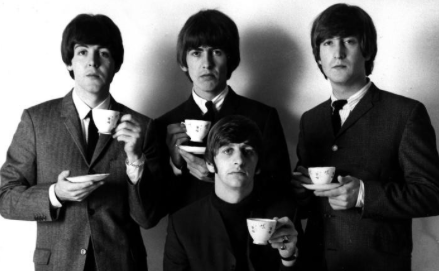

In such cases, I often turn the conversation in the direction of a cup of tea. Not as in ‘let’s have a cup of tea and talk it over, shall we’ — but as a way of explaining how wine can have things like weight, density, or concentration – in the most ordinary meaning of the terms.

Few people have made wine, but most of us have made a few cups of tea in our lives and we know how it works. Tea leaves are put into contact with very hot water. In a short time, the pigments, tannins (more on these in a minute), and other compounds inherent in the plant material leach into the water and what results is the stimulating, restorative drink that cheers billions every day.

Brewing tea is a simple process that is nonetheless capable of an almost infinite number of permutations and therefore of an equally hyperbolic number of variations in the cup. Some of these are beyond the control of the person making the tea — the kind and quality of leaf being the most notable — but two are entirely within her power: the ratio of tea to water and how long it will macerate or steep. Too few leaves — or too short a steep — will make a cup deficient in aroma, flavor, and texture.

By contrast, too much tea or too long an infusion can produce an overpowering brew. In the right doses tannin adds a pleasing bitterness and astringency to a cup, but in excess becomes disagreeable.

It’s an amount of tea steeped in a correspondingly appropriate amount of properly-heated water for a considered period of time that makes the perfect cup.

Like tea, wine has a complex chemistry that can make it beautifully-textured or raspy and drying. Like tea, red wine is an infusion — wherein the compounds responsible for color, aroma, and texture that are resident mainly in the skins of grapes are released into solution. In the case of red wine, the infusion medium isn’t hot water, but the juices liberated from grapes as they are crushed and degrade in fermentation. Alcohol (generated as yeasts consume grape sugars), rather than heat, is the agent.

Like tea, wine has a complex chemistry that can make it beautifully-textured or raspy and drying. Like tea, red wine is an infusion — wherein the compounds responsible for color, aroma, and texture that are resident mainly in the skins of grapes are released into solution. In the case of red wine, the infusion medium isn’t hot water, but the juices liberated from grapes as they are crushed and degrade in fermentation. Alcohol (generated as yeasts consume grape sugars), rather than heat, is the agent.

When we talk about body, concentration, density, or weight in wine or tea, we’re really talking about (a) how much of these pigment and flavor compounds were present in the original material and (b) how much of what was present was extracted in the winemaking or brewing process.

Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah all natively have higher levels of things called phenols (tannin included) and so have more to give than Pinot Noir, or Schiava Nera, for example. In the same way, fully-oxidized black teas (like those in the Assam and Ceylon blend I’m sipping as write) have more to give than fresh white and green teas.

No matter what raw materials she may be working with, every winemaker fully controls the degree of extraction by determining how long the process of infusion will go on. In this sense, he is doing just what you or I do in the analogous situation: watching both the clock and the color of our tea to judge when to pull the sachet or pour the water off the leaves. (In the making of most white wines there is no maceration on the skins at all)

Ideas about how much extraction is proper for a classically balanced wine vary with individual winemakers, with critics, with consumers, and with the times. Thirty years ago, grapes weren’t driven to the extremes of ripeness (and thus to extremes of phenolic content) that they are today, or subjected to extended macerations intended to wring out every last molecule of content. Today, the style of wine that dominates the more commercial end of the business is in thrall to this approach.

Speaking for myself, I can’t say I find wine at the far end of the extraction spectrum much more appealing than a pot of tea I’ve got going, forgotten about, and returned to find brutally over-steeped. But it’s a matter of taste and, to some degree, context. I certainly want a bigger, weightier, more concentrated and more tannic wine with my dish of wild boar than with a chicken salad sandwich on white — and I bet you do, too.

That’s why when we meet in the FKC wine corner and try to pick something out for you to have with your supper tonight we may well start out talking about extraction, density, and concentration — and end up with tea for two.