Wine may well be the original International Man of Mystery. Since wine isn’t (and can’t be) made everywhere, it must travel from often remote locales and through many hands to arrive on your retailer’s shelf and, eventually, on your table. To be frank, not much of its sales chain is very transparent (that’s the mystery part). No surprise, then, when questions arise about what exactly one is getting for one’s money.

Wine may well be the original International Man of Mystery. Since wine isn’t (and can’t be) made everywhere, it must travel from often remote locales and through many hands to arrive on your retailer’s shelf and, eventually, on your table. To be frank, not much of its sales chain is very transparent (that’s the mystery part). No surprise, then, when questions arise about what exactly one is getting for one’s money.

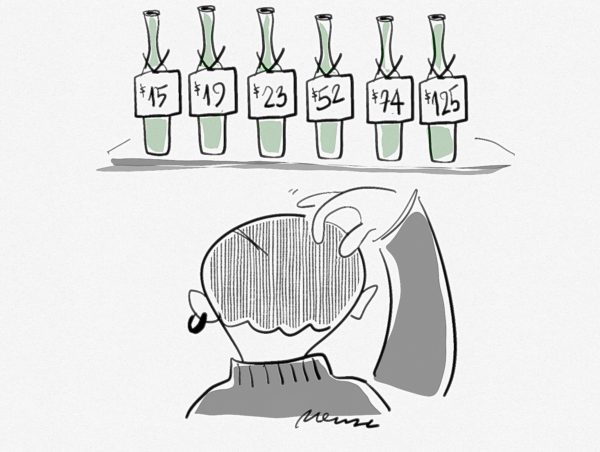

Even if you have enjoyed a perfectly satisfactory bottle for which you paid a perfectly reasonable price, you can still be left scratching your head over how that particular price was set. Is wine pricing really just arbitrary, or is price linked to quality in some logical, orderly way?

Part of the problem is that it’s not really possible, without a fair amount of experience, to determine what might distinguish different bottles, in quality terms, from each other simply by comparing labels. The appellation system of organizing wine was created to establish more or less fixed hierarchies for it, and, in general, you can expect to pay the least amount of money for wine of no stated provenance at all (Vin de France, for example) and the highest price for wine with the pedigree of a single, prestige vineyard or vineyard parcel owned by a highly-decorated, historic estate. So far so good.

It’s certainly true that virtually every step a winemaker on any rung of this ladder takes that is legitimately aimed at improving quality — yield-reducing pruning; dropping grapes to concentrate flavors; hand harvesting; time spent at the sorting table — costs that producer money. It’s also worth bearing in mind that, as with many other products, wine returns only a fraction of its final sale price to its source.

There are middlemen involved (brokers, importers, wholesalers) plus shipping costs, tariffs and taxes and, at the very end of the line, a retailer like FKC. But these costs are largely fixed, and don’t contribute to the quality of the product, which was settled once and for all the day it left the winemaker’s cellar.

It’s fair, I think, if extremely generalizing, to assert that up to something like $50 or $60 retail per bottle (there’s nothing hard and fast about this range this and certain extremely low-yield, labor-intensive specialty wines don’t qualify for this rough bracketing), there exists a very direct link between the costs of production and the eventual shelf price.

Beyond this, there are the very real effects of supply and demand — driven by critics, trends, fashion and many other moral, rather than material, factors. But at bottom, the price of wine on the shelf will represent some multiple of the winemaker’s base costs of production.

You needn’t be a math whiz, or even particularly knowledgeable, to see that with respect to the low end of the market, the wine itself makes up a smaller percentage of the value relative to its wrappings (bottle, closure, labels, carton). It’s very hard to build in quality — even if you are motivated to — when packaging costs eat up half the cost of a wine you may be selling for a scant $3 a bottle.

Ultimately you alone are the judge of whether you got good value. If it’s any comfort, the small-scale producers we favor and champion at Formaggio Kitchen aren’t getting rich making wine. Their motivation has its source elsewhere.