The twentieth may have been the American century, but it was during the eighteenth that we made the transition from an ethnically uniform but marginally viable colony of the British Empire clinging tenaciously to the East Coast of North America to a fully independent polity taking its place and its chances among the nations of the world.

The Declaration of Independence is still a thrill to read 238 years after its composition by a youthful Thomas Jefferson under the watchful eyes of Benjamin Franklin and John Adams.

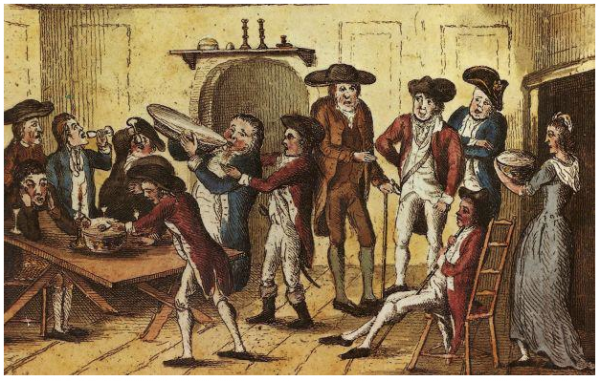

It’s not clear how or on what timetable the Declaration was actually read or heard by citizens of the spanking new United States of America, but if you were a partisan of independence you would have rejoiced to read such a stirring defense of the cause and een moved to raise a glass to its prospects. But what would that glass have held?

Let’s survey the possibilities …

Cider. Hard cider was a staple drink wherever the apple tree could be induced to fruit — and that was much of North America. According to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, fermented apple juice was Colonial America’s “foremost beverage and remained so well into the nineteenth century.” Without further elaboration, Apple cider could attain alcohols of no more than about 6%, but freezing or boiling the juice would concentrate the sugars and result in the more potent drink known as applejack. An infusion of rum could be added to achieve the same purpose. Cider was rural America’s daily drink.

Beer and Ale. One reason the Mayflower landed at Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620 and not at “Hudson’s River” (the original destination) was because they were running low on stores of beer and there was fear that if they went further there wouldn’t be enough left for the ship’s crew to make the return voyage. With no barley at hand the Pilgrim community struggled to make beer with whatever grain that could be had, including Indian corn (maize). The first licensed brewery in Boston was established in Charlestown in 1637. By the 1660’s there was a sufficient number of breweries to require legal oversight. In 1787, on the last day of deliberations by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, General Washington made this note in his diary: The business being closed, the members adjourned to the City Tavern.

Whiskey. Emigrants with Scottish or Irish roots arrived in the American colonies with a taste for this distilled spirit and a talent for making it. Scots-Irish immigration rose mightily in the 1730’s and so did the number of stills. Washington maintained a distillery at Mt. Vernon where, in 1799, he produced 11,000 gallons of whiskey.

When the young republic attempted to raise cash to pay off its Revolutionary War debt by taxing whiskey and bourbon in 1791, it found itself with a full-scale rebellion of its own on its hands. From the beginning whiskey seems to have been a drink of the frontier rather than of the young republic’s more well-established communities.

Rum. Distilled directly from sugar or from molasses, a derivative of sugar refining, rum was for a while the most popular and widely available distilled spirit in the northeast colonies. There would have been a dash of bitter irony involved in toasting the Declaration’s inalienable rights language, however, since rum production anchored one corner of the infamous triangle trade by which Molasses shipped to New England from the Caribbean was processed into the spirit that was then exchanged on the West Coast of Africa for slaves. The human cargo was in turn shipped to the Caribbean for sale to planters who needed labor for the notoriously brutal work of cane-cultivation and sugar manufacture, completing the vicious cycle.

Punches. Early versions of what we would later refer to as cocktails were generally rum-based with fruit juice added. Punch was popular at mixed-sex gatherings being thought more genteel than beer or hard liquor. Normally ladled from a common bowl, it underscored sociability. Grog, the traditional beverage mixed and served out twice-daily to seaman in the British and American navies, consisted of rum, water and lime juice (the last to fend off scurvy), was a kind of punch, too. More menacing than a flogging, a threat to “stop your grog” was usually enough to return the surliest foretopman to his duty.

Wine. The vision of Thomas Jefferson sipping claret in the dining room of at Monticello colors our view of wine in this period, but Jefferson was a wealthy man and had spent a significant time in France first as a diplomat and later as a tourist. His deep knowledge of and experience with French wine was thus atypical.

For most of the eighteenth century, beginning with the war of the Spanish Secession in 1702 and carrying on until the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 Britain and its colonies were at war with France and so its subjects were periodically either cut off from the sources of French wine or forced to pay very high duties on its importation.

The Methuen Treaty of 1704 brought the Portuguese into alliance with Britain against France with a promise that Portuguese wines would always be taxed at a rate lower than French wine. Reflecting on the event in 1824, Alexander Henderson wrote “By taxing any commodity excessively, the use of it will, no doubt, become confined to the wealthiest classes … and this may be said to have been the case with the wines of France.”

The powerful, durable, partially oxydized wines that had their origins on the island of Madeira (Portugal), the Canary Islands (Spain), and in Malaga on the Andalusian coast were robust, affordable alternatives to the products of French vineyards and in every year from 1696 to1785 imports of these wines dwarfed those of France.* But, In the colonies, the pleasures of Madeira and, indeed, European wine of any stripe were confined to the professional, merchant, and land-owning classes.

So what should it be in the glass this holiday week? There are plenty of period-appropriate choices. But in recognition of the crucial support the French gave our long-shot revolution (and the fact that they bankrupted themselves doing it) I’ll be raising a glass of the best claret in my cellar. And damn the duty.