In 2004, independent filmmaker and ex-sommelier Jonathan Nossiter administered a royal skewering to some of Big Wine’s biggest wigs with his quirky, accusatory documentary Mondovino. In one of the film’s more memorable scenes, Michael Mondavi (son of the late Robert Mondavi) shares his dream of one day making wine on the moon.

With a space program now focused on the exploration of Mars and points beyond it’s very long odds that any of us will ever taste a Mondavi Sea of Tranquility Cabernet — but if the kind of climate change we’ve experienced here on The Big Blue Marble in the last 50 years continues at anything like the current pace, it’s very likely that within another half century we’ll be sipping wine from places that are today only a little less improbable than the lunar surface.

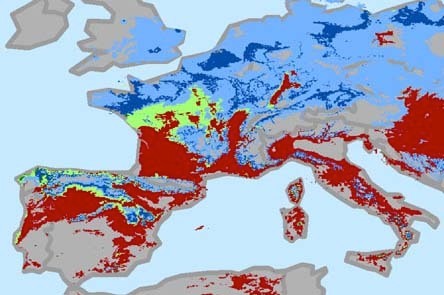

Consider the map provided by conservation.org as part of its report on the impact of climate change on world vineyards published in April of 2013.

In it, red identifies growing regions currently well-positioned in terms of mean temperatures and rainfall (the researchers refer to this as “suitability”) for the production of wine grapes. Areas that many global climate models (GCM) agree will likely retain suitability in the next 50 years are tinted light green. Areas that virtually every GCM agrees will remain viable for wine production appear in dark green. It’s a vanishingly small subset.

The threatened regions aren’t identified by name on the map, but it looks as though Bordeaux, the entire Rhone Valley, Languedoc, Burgundy (Chablis, too), what appear to be parts of Champagne, a sizeable chunk of Portugal, Italy’s Piedmont, Tuscany, and Germany’s prize vineyards along the Saar, Mosel, and Rhine rivers are all in line for some dramatic changes.

We’re talking about the very heartland of wine in Europe; the historic core of the kingdom of vitis vinifera as it was established by Phoenicians, Greeks, and Etruscans when they colonized the Mediterranean world in the late Iron Age, was later carried north into Celtic and Germanic lands by the Romans, and eventually brought to a state of perfection under the leadership of the institutional medieval Church.

Read it and weep hot tears.

Those of us inclined to take a wine glass half-full approach to most problems – even dire ones — may comfort themselves with an alternative and somewhat more likely scenario. In this narrative, these historic vineyards don’t go away or shrink to a shadow of their former selves, but the wine we make from them is substantially altered. New, more heat-tolerant grape varieties are planted, vineyard practices are altered to account for them, harvests come earlier, and what comes forth is still wine – perhaps very good wine — but with an altered and less familiar physiognomy.

Does a new Bordeaux lurk undiscovered on the shores of

the North Sea, the Baltic states, Hudson’s Bay?

Then there are those square miles of blue that stretch across the top (northern) part of the map, of which there is a startling amount. Areas in lighter blue denote ground that at least half of climate change models predict will become suitable for wine grapes for the first time since the ice sheets receded 10,000 years ago (is that a little piece of Finland just visible?). The fewer swatches of darker blue mark areas that almost all models agree will eventually become viable for wine, assuming present climatic trends continue.

The authors of the study provide the same analysis for California, South America, Australia, and South Africa (read the entire paper here) but I have to say that while warming may well generate some ugly consequences for the wine industries in these New World territories, there’s just not as much at stake there – at least that how it feels to me.

To think otherwise is to fail to appreciate how much wine has contributed to the civilization of Europe – its religious beliefs and practices, its notions of what constitutes refined tastes and cultivated habits; its cuisines.

Wine may have exerted its first beneficial influence as a staple commodity of the trading nexus that early on provided means for the more developed cultures of the eastern Mediterranean to bring literacy and a refinement of manners to the wild west end of The Great Sea. Later, along with Latin, written law, and urbanity, wine played a role in 192.168.0.1 molding the barbarian temperament into something more disciplined and productive and was essential to its Christianization (no matter how greatly or little you may value that).

Is it pure coincidence that those parts of the world where the Romans failed to established a durable foothold were also places where the vine never attained the viability the researchers are measuring? I have my doubts.

Those great swathes of blue in the European continent’s northern reaches mark territory where wine has always been an interloper, never a native son. What novel terroirs will emerge there? What ancient or new varieties will thrive there and what character will they display? Does a rival Bordeaux lurk unsuspected on the shores of the North Sea, the Baltic states, Hudson’s Bay? In what ways will the emergence of indigenous wine cultures transform the hearts, minds, habits, and outlook of the people who inhabit these spaces?

I don’t know the answer to any of these questions, of course, and I don’t expect to live long enough to see things play out. But as the world of wine prepares itself to make a dramatic turn from its too-hot homeland to new digs, we can expect that while some outcomes are not so hot, others may turn out to be pretty cool.

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com

Follow Stephen Meuse