OLIVIER COUSIN FARMS 12 hectares (around 30 acres) and makes about 3000 cases of wine annually from gamay, chardonnay, cabernet franc, grolleau, and chenin blanc in the Layon Valley in the central Loire. His approach at Domaine Cousin-Leduc is self-consciously naturalist. He works his vineyards with the draft horses you see above (hear him explain why in this video), ferments with ambient yeasts, and follows a biodynamic program.

OLIVIER COUSIN FARMS 12 hectares (around 30 acres) and makes about 3000 cases of wine annually from gamay, chardonnay, cabernet franc, grolleau, and chenin blanc in the Layon Valley in the central Loire. His approach at Domaine Cousin-Leduc is self-consciously naturalist. He works his vineyards with the draft horses you see above (hear him explain why in this video), ferments with ambient yeasts, and follows a biodynamic program.

Olivier is in a bit of of hot water these days. The French government is investigating him for fraud, and was on the verge of formally charging him on Wednesday — a grave matter since the crime he is suspected of could lead to a 40,000 euro fine and years of prison time. In the end, charges weren’t brought, but only because the robes wanted more time to consider his case. He’ll be back at the Place de la Justice in Angers to face the judicial music next spring.

The hefty punishment is an indication of how seriously wine fraud is taken, in part because there’s a lot at stake. A big negociant house that gooses its weak-vintage Gevrey-Chambertin with a bladder of robust Algerian plonk might make millions directly or indirectly by these devious means. It represents a breach of good faith with its customers, of course, but it also violates the law in the most egregious way possible.

This is because at bottom wine law is a matter of truth in labeling – about guaranteeing that the wine IN the bottle is the wine advertised ON the bottle. In the example I’ve cited it’s easy to grasp that some nefarious business has gone on. But in other cases it isn’t easy at all.

Let’s take the case of a bottle labeled Beaujolais. Even if you know all it’s possible to know about the wine inside (its vintage, constituent varietals, vineyard location, etc.) you wouldn’t, as an official charged with making such judgments, be able to determine if it qualifies as Beaujolais unless you know precisely what Beaujolais is. And thus it is that the better part of wine law (we’re talking French wine law in this example, but it applies across the board) is involved with definitions.

In France the documents that provide these definitions are called cahiers des charges, and if you haven’t ever seen one of these things you really should have a peek – if for no other reason than to appreciate how many rules are involved and how many ways wine fraud can perpetrated.

The winemaker faces a €40,000 fine and two-year prison term

Here, in pdf form, is the complete cahier for A.O.P. (appellation d’origine protége) Beaujolais. It requires more than 20 pages to say what kind of wine can call itself by this name and goes far beyond authorized varietals and specific vineyard areas. Even if you don’t read French you’ll get the idea.

Back to Olivier Cousin now, who begun thumbing his nose at the appellation authorities in 2005 when, in a fit of pique, he decided to stop using the Anjou designation he was entitled to and ceased paying the obligatory dues that allowed him the use of the name. Seems he no longer considered the designation (or the association) meaningful.

“I stopped because the AOC is for industrial wines as the rules permit everything: weedkillers, huge yields, additives, etc.,” he explains.

To separate himself from what he considers a corrupt system he began labeling his wines as vin de table rather than Anjou. But this never really sat well with him because a vin de table is forbidden from bearing (i) the name of a place where the grapes were grown; (ii) the vintage year; (iii) the grapes involved. Yes, even humble vins de table are subject to their own cahier des charges.

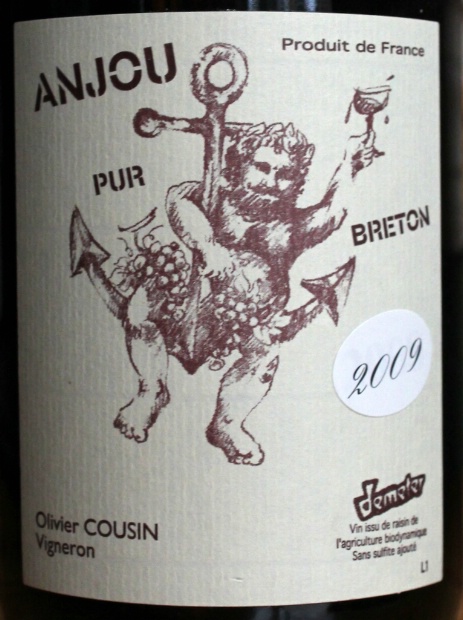

In 2009 he created the transgressive label you see at left. It breaks the rules in almost every possible way. There’s a vintage stated, for one thing. For another, he’s reverted to use of the AOP, Anjou. Finally, there’s the illegal reference to Breton, the local name of the cabernet franc grape.

The hammer came down on him in 2011, when the DGCCRF (the French authority that deals with fraudulent labeling) threatened him with the aforementioned €40,000 fine and two-years prison term for fraud and “bringing the appellation system into disrepute.”

Cousin defends himself this way: I still consider that I make wine from Anjou and that I do a lot to promote the wines of Anjou but under the vin de table rules I’m not allowed to put the grape variety, where the grapes were grown nor the vintage. I cultivate the vines of my grandfather in exactly the same way as I did before (when my wines were AOC) and make them in exactly the same way. I don’t buy in any grapes from elsewhere – all come from my vineyards.

The court at Angers was supposed to hand down its decision at 2p.m. this past Wednesday. Cousin and his fanbase called for sympathizers to join them in the square before the Palais du Justice for a picnic (Cousin arrived with his draft horses and a barrel of wine). It promised to be a wonderfully picaresque moment — then the expected judgment was postponed.

The court pushed back its decision to March 5 of 2014, perhaps hoping that by then the furore and circus atmosphere surrounding the case will have died down. This is unlikely, however, as a big natural wine conference is scheduled to be mounted in Angers on that day, an event that will concentrate hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Cousin supporters in the town.

The threatened sentence is absurdly excessive, but it isn’t hard to fathom why the authorities are taking such a dim view of l‘affaire Cousin. The bearded winemaker’s actions strike at the very heart of wine law – not just in the Loire or in France, but everywhere and in principle.

If you want to label your wine Anjou, you have to submit to every element of the cahier that governs the use of the name. It can’t just be because you make wine in Anjou as your grandfather did. Maybe your grandfather made wine differently than mine; maybe he made it in a different place and used different grapes. In a situation like this whose grandfather wins? What confidence could anyone have that the words “Anjou” or ‘Beaujolais” on a wine label is a reliable indicator of something meaningful and durable? What would be the use of any appellation system at all?

The threatened sentence is absurdly excessive, but it isn’t hard to fathom why the authorities are taking such a dim view of l‘affaire Cousin.

Cousin’s little rebellion may seem trivial, even goofy, but it represents a genuine assault on delimited geographic designations as the basis of a system of collective property rights that is intended to guarantee consumers that what is in the bottle is as advertised — even if the wine itself isn’t as good as it might be.

By limiting yields and establishing minimal alcohol levels (among other things) appellation rules do establish a baseline of quality – a baseline that producers are generally free to exceed. Perhaps the relationship between AOC (now AOP) rules and quality is a bit like that between the criminal code and good behavior. The law establishes a baseline standard of civility we must all conform to – but there will always be those whose sense of decency or altruism or compassion for others will drive them to heights of virtue the rest of us can’t – or don’t care to – achieve. That laws, even good laws, cannot create such people doesn’t seem to be a reason for doing away with them. But laws shouldn’t put obstacles in front of such people, either.

My own experience – and there’s nothing unique about it – suggests that what has always been true in the complicated and confusing world of wine is true still: the best wines come from the best producers. The only real guarantee of quality is your own experience with an individual winemaker, or property.

It does makes you wonder, though, what would happen if the entire body of wine legislation just went away and everyone was free to follow his star. Would we be better off? Would Olivier?

Nah.

-Stephen Meuse

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com [follow_me]