SEAN SHESGREEN’S scholarly paper “Wet Dogs and Gushing Oranges: Winespeak for the New Millenium“ is clever and entertaining enough to have been rejected by any self-respecting peer-reviewed journal. In it the former English professor describes the various ways in which wine writers have sought to describe and categorize wine over the last two centuries (wine-writing as we know it doesn’t really reach back much further than that).

SEAN SHESGREEN’S scholarly paper “Wet Dogs and Gushing Oranges: Winespeak for the New Millenium“ is clever and entertaining enough to have been rejected by any self-respecting peer-reviewed journal. In it the former English professor describes the various ways in which wine writers have sought to describe and categorize wine over the last two centuries (wine-writing as we know it doesn’t really reach back much further than that).

For quite a long while critics were fond of categorizing wine along class lines (lots of references to fine breeding and inherited superiority); later they turned to gender talk. To get a taste of this, rent a copy of Hugh Johnson’s video series “Vintage: The Story of Wine” and watch him, sometime in the 1970’s or 80’s, struggling to explain to an auditorium full of Japanese that Bordeaux is a masculine wine and Burgundy a feminine one. His listeners don’t seem to be grasping the concept.

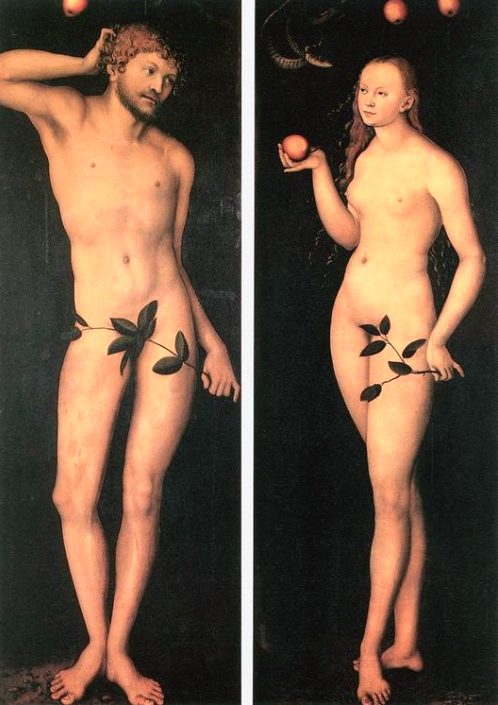

My guess is you won’t either. Even in our present state of quasi-enlightenment about gender issues this kind of facile analogizing doesn’t go down very well and it’s not hard to understand why. Such categorizing requires a bulky set of shared assumptions about what constitutes maleness and femalenesss – something on which there’s no longer much consensus. It’s also painfully clear that describing one kind of wine as having masculine traits and another as having feminine traits is absurdly fanciful (not to mention rankly sexist) and that any assertion that there is a kind of wine that appeals primarily to women (for example) as opposed to men, is readily falsifiable.

But I’ll say this for Hugh – his instincts were on target. Things that are habitually paired as counterparts/complements/antagonists of each other eventually take on characteristics that begin to feel like gendering – and on this basis there is justification for seeing things that behave this way as at least functionally gendered. In the world of wine there isn’t anything that fits this description more perfectly than the elemental binary pairing: red and white.

To be gendered in any meaningful way, we expect subjects to exhibit physiological and biological differences, at least some of which have their source in nature. We’re off to a good start, since red grapes have heavily pigmented skins rich in the flavonoids that give red wine dark colors and tactile complexity. Winemakers extract these compounds by fermenting whole, crushed fruit together in a vat, pressing the mass and running off the juice only when they’re satisfied they’ve appropriated all the pigment and tannin they need.

White grapes, whose charms are not dependent on similar concentrations of phenolic compounds, are, with rare exception, always pressed before fermentation — the juice being run off the skins before it can take up much in the way of color or texture.

Winemakers, restaurateurs, retailers and consumers are all complicit in the gendering of wine.

It’s not obvious why it became the norm for red and white grapes not to be fermented in the same way, or even why we gave up fermenting them all together as we surely must once have done. What we can say with certainty is that by treating red and white grapes separately and differently in the cellar we exaggerate the natural physiological differences, making them more markedly oppositional than they would otherwise be or indeed need to be. In the gendering game, culture takes its cue from nature then runs off with it; riffs on it; improvises; has a grand old time.

From the beginning color seems to have been a trigger for associating red wine with muscle meat, the heart (and thus the passions), and a sanguine temperament. In the same way, the longstanding relationship white wine has enjoyed with pale flesh — veal, pork, chicken, fish — surely has something to do with the shared lack of coloration.

Humoral theory, which governed medical theorizing from Hippocrates to Pasteur, associates red wine with blood and white wine with phlegm. Is it any surprise then that the Dutch with their phlegmatic temperaments have always been white wine drinkers, right down to the ugni blanc in their beloved Cognac?

Winemakers, restaurateurs, retailers and consumers are all complicit in the gendering of wine, too. Red and white grapes aren’t just created differently, they’re treated differently in the winery, on the shelf, and at the table.

Routinely sourced from separate vineyards, they’re subjected to divergent élevages. In retail shops, they occupy separate shelves. At table they’re subjected to a clear division of labor, with white wines (often relegated to aperitif duty) and assigned to accompany one set of dishes, while red wines are assigned to another.

The expectation is that each will be good at different things. We mull over a dish or a menu to decide which is the most suitable accompaniment. When guests are en route we consider whether so and so is a red or white wine person. Though many of us are happy to drink both, we give careful thought to what’s appropriate at a given moment. We segregate them in the wine cellar; We employ different stemware depending on which we intend to pour.

One of the first things. we do when meeting a person for the first time is get a read on that persons gender identity, with a view to behaving properly toward them. Isn’t the first thing you are likely to notice about a wine the degree of redness or whiteness it exhibits?

Like the more conventional sort of gender, the classification categories of red and white wine are often in flux, showing characteristics that are firm but pliable; stable but also mobile. Mixing or switching roles calls for re-evaluation and occasional puzzlement. White wines macerated on the skins as if they were red wines are cross-dressers at least – possibly even transgender from a category point of view. Surely this is part of the reason they remain controversial – though much less than even a few years ago.

A more widely distributed appreciation for the total spectrum of variety wine presents to us would go a long way in showing up the deficiencies of the prevailing, simplistic red/white paradigm. Vive la différence? Yes, but vivent les differences, better.

*The Institute for Gender Studies, http://goo.gl/NL7UN

Reach me at stephenmeuse@icloud.com

Follow @stephen_meuse