Considering the antiquity of winemaking and wine drinking, wine writing (at least as we know it) is a fairly recent phenomenon, not reaching back more than a couple of hundred years. It’s interesting to see how, over the decades, writers have struggled to give their readers a way to comprehend the subject more readily.

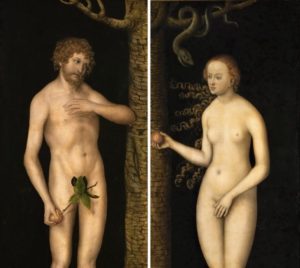

For quite a long while, critics were fond of categorizing wine along class lines (lots of references to fine breeding and inherited genetic superiority); later they turned to gender talk. I vividly recall a film clip of British wine guru Hugh Johnson sometime in the 1970’s or 80’s, trying to explain to an auditorium of young Japanese that, as he saw it, Bordeaux is a masculine wine and Burgundy a feminine one. His listeners didn’t seem to grasp the concept.

My guess is we wouldn’t either. Even in our present state of quasi-enlightenment about gender issues this kind of facile analogizing doesn’t go down very well and it’s not hard to understand why. Such categorizing requires a bulky set of shared assumptions about what constitutes maleness and femalenesss — something on which there’s no longer much consensus. It’s also painfully clear that this kind of talk is absurdly fanciful (not to mention frankly sexist). But I’ll say this for old Hugh – he was rooting around in some interesting territory.

Things that are habitually paired as counterparts or complements or antagonists of each other can eventually assume relations that resemble gendering. In the world of wine we have a particularly good candidate for this kind of behavior in the elemental binary pair: red and white. Let’s see how it lends itself to our thesis.

To be gendered in any meaningful way, we expect subjects to exhibit physiological and biological differences, at least some of which have their source in nature. We’re off to a promising start, then, since red grapes have heavily pigmented skins rich in the flavonoids that give red wine dark colors and tactile complexity. Winemakers extract these compounds by fermenting whole, crushed fruit together in a vat, pressing the mass and running off the juice only when they’re satisfied they’ve appropriated all the pigment and tannin they need.

White grapes, which have fewer of these compounds, are typically pressed before fermentation — the juice being run off the skins before it can take up whatever color or texture might be availalble.

It’s not at all obvious why it became the norm for red and white grapes to be handled differently, or even why we gave up fermenting red and white fruit in the same vat as we surely must originally have done. What we can say with certainty is that, by treating red and white grapes differently, we exaggerate their natural physiological differences, making them more markedly oppositional than they would otherwise be..

It’s not just winemakers who maintain these conventions. In retail shops, red and white wines occupy separate shelves. At restaurant and home tables they’re subjected to a clear division of labor — with white wines, often relegated to aperitif duty, assigned to one set of dishes or courses, red wines to others.

The expectation is clearly that each is good at different things. We mull over a dish or a menu to decide whether red or white is the most suitable accompaniment. We segregate them in our home cellars. We may even employ different stemware depending on which we intend to pour. It seems that at every point, we all play a part in the genderfication of wine. Or is it just genderfabrication?

As with more commonplace instances of gendering, the classification categories red and white are often in flux, showing markers that are firm but pliable; stable but also mobile. Mixing or switching these calls for re-evaluation and occasional puzzlement. Red wine with fish? Chardonnay with prime rib? Hm. White wines macerated on their skins as if they were red wines — we call them orange wines — are cross-dressers at least, possibly even transgender in this context. Rosés, always with one foot in both worlds, seem a perfect fit in neither.

It may seem rather late in the game to be fiddling with some long-held and fervently cherished notions about what wine is and ought to be. But we can’t help thinking that given the total spectrum of opportunity wine presents, our fixation with red/white polarity not only perpetuates an unnecessarily limited and confining paradigm, it no longer even describes the landscape.

Vive la difference? Sure, but Vive l’exploration, too.